Background

I was awarded the Easterfield Prize from the NZIC in 2021, which is given to a chemist within 12 years of their first academic appointment. As part of the prize, I travelled to the United Kingdom for a lecture tour with the Royal Society of Chemistry.

In May 2024 I visited four universities in Scotland, England and Wales – Heriot-Watt University (Edinburgh), University of Glasgow, University of Southampton and University of Swansea. The four universities were all rather different, from the relatively new “plate glass” university of Heriot-Watt (founded as the School of Arts of Edinburgh but gained university status in 1966) to the historic University of Glasgow (founded in 1451). Heriot-Watt had a strong contingent of early-mid career researchers, including those conducting some interesting (and geographically apt!) whisky research. A highlight at the University of Glasgow was that I was asked to sign the visitor book for all people that give lectures in the chemistry department, which included the signature of Linus Pauling, among other famous names! Southampton University is known for its strong basis in chemical education and I was pleased to be able to spend some time with one of their teaching fellows exploring some of the differences between the UK and NZ systems. Swansea University Chemistry Department stopped offering a chemistry degree in 2004 but the degree was reestablished in 2017, and the department has wonderful undergraduate laboratories and enthusiastic research staff. While in Swansea I was also very kindly hosted by the Southwest and Central Wales branch of the RSC for their AGM and annual dinner.

On the whole it was a diverse and very enjoyable tour, meeting with existing colleagues and forming new relationships. I am very grateful to the NZIC and RSC for providing me this opportunity to share an overview of my group’s research activities, which I give in more detail below.

Introduction

Heterogeneous catalysis, in which the catalyst and reactants exist in different phases, typically involves solid catalysts interacting with gas- or solution-phase reactants. This field is central to major industrial processes including ammonia synthesis,1 catalytic converters2 and fuel cells3 while also underpinning emerging sustainable technologies such as green hydrogen production4 and reduction of carbon dioxide to hydrocarbons and alcohols.5 Traditional heterogeneous catalysts based on extended metallic surfaces generally require elevated temperatures and/or pressures to achieve acceptable reaction rates and yields. However, recent advances have demonstrated that superior catalytic performance can be achieved through two complementary approaches: applying an electrical potential to overcome reaction barriers (electrocatalysis), and exploiting quantum size effects, high surface-area-to-volume ratios and unique surface sites in nanoparticulate catalysts (nanocatalysis). Computational modelling is a useful tool for elucidating atomic-scale reaction mechanisms and enabling rational catalyst design in both fields. However, electro- and nanocatalysis each present distinct computational challenges that extend beyond those encountered in conventional heterogeneous catalysis. This article briefly describes these challenges and presents our group's approaches to addressing them.

Electrocatalysis

Electrocatalysis shares many features with conventional heterogeneous catalysis, including adsorption, diffusion, and desorption of species on solid surfaces, each of which must be accurately modelled. Furthermore, reactions typically proceed via multiple elementary steps with competing mechanisms, where the energetics of the individual steps determine overall activity. The electrochemical environment introduces additional complexity, namely the presence of charged species, an electrified solid-liquid interface, and solvents that often participate directly in the reaction.6 Consequently, specialised computational tools are required. A hierarchy of such methods exists, ranging from simple to sophisticated, with corresponding trade-offs between computational cost and accuracy. Method selection depends on both the complexity of the electrocatalytic reaction and the nature of the electrocatalyst itself.

Hydrogen evolution reaction

The hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) represents the simplest electrocatalytic reaction and is therefore an interesting test case for computational methodology:

2H+ + 2e- → H2(g) (1)

The cathode serves dual roles – it both supplies electrons and catalyses the reaction. Traditional HER catalysts are Pt-based materials,7 which exhibit high activity but are scarce and prohibitively expensive for widespread use. This has motivated intensive research into Earth-abundant alternatives.8

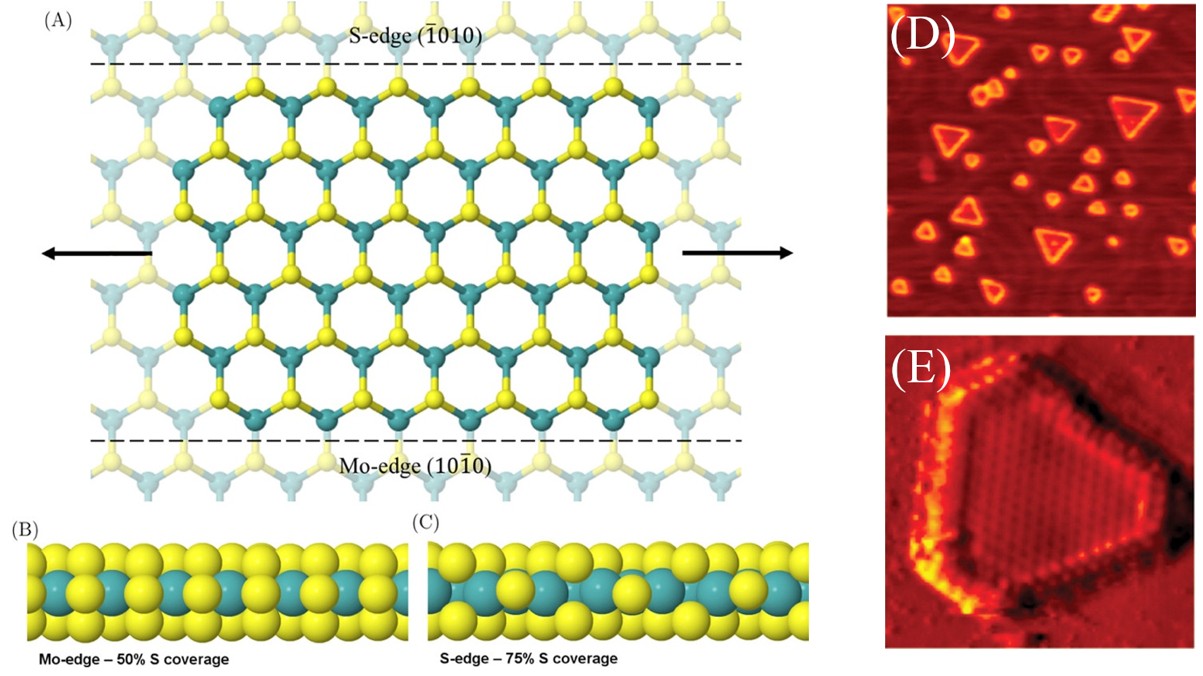

Molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) has emerged as a promising HER catalyst. Structurally analogous to graphite, it consists of weakly bound layers,9 that can be exfoliated to yield 2D, single-layer catalysts (Fig. 1a-c). When synthesised as nanoflakes, MoS2 exposes conductive edge sites (Fig. 1d-e), which have been shown to be relatively active towards the HER.10-12

Fig. 1. (A) Structure of single-layer MoS2. Structures of the (B) Mo edge and (C) S edge at S coverages that are typically found under industrial conditions. Reproduced with permission from reference 15. (D) STM image of MoS2 nanoparticles on Au(111), 470 Å by 470 Å. (E) Atomically resolved MoS2 particle, showing the predominance of the sulfided Mo-edge (60 Å by 60 Å). Reproduced with permission from reference 10.

The 2D structure of MoS2 enables diverse structural modifications to tune HER activity. The simplest approach involves introducing a secondary supporting material.13,14 To understand how such modifications influence activity, a detailed mechanistic understanding of the HER itself is required. We therefore investigated the HER on MoS2 supported by two distinct materials: a Au(111) surface and graphene.15

Understanding electrocatalytic HER on supported MoS2 requires elucidating both the elementary reaction steps, and how the electrochemical environment affects each step. The initial Volmer step involves proton adsorption at the electrode surface, where it combines with an electron to form an H adatom (*H):

H+ + e- → *H (2)

Subsequent H2(g) formation can proceed via two mechanisms. In Tafel desorption, two H adatoms combine following a second Volmer step:

*H + *H → H2(g) (3)

Alternatively, Heyrovský desorption involves an H adatom combining with a proton from solution and an electron from the electrode:

*H + H+ + e- → H2(g) (4)

Note that the Tafel and Heyrovský mechanisms are the electrochemical analogues of Langmuir-Hinshelwood and Eley-Rideal reactions in heterogeneous catalysis. Complete understanding of the HER mechanism requires modelling both thermodynamics and kinetics of each of the Volmer, Tafel, and Heyrovský steps.

A key challenge in modelling the thermodynamics of the Volmer and Heyrovský steps is calculating the energy of the proton-electron pair, which is non-trivial in periodic density functional theory (DFT), which is the workhorse of computational heterogenous catalysis. However, in 2004, Jens Nørskov et al.,16 introduced the computational hydrogen electrode (CHE) approach, which elegantly circumvents this problem and has since become the standard method in computational electrocatalysis (>10,000 citations to date). The CHE uses the standard hydrogen electrode (SHE) as reference:

2(H+ + e-) ⇌ H2(g) (5)

At U = 0 vs SHE (where U is the electrode potential on the SHE scale), the reaction in Eq. 5 is in equilibrium (ΔG = 0). As such, the Gibbs energy of the proton/electron pair, G(H+ + e-), is equal to half the Gibbs energy of an H2(g) molecule, G(H2), which is readily calculated using standard computational chemistry software. Furthermore, the CHE captures the effect of electrode potential on the reaction Gibbs energy through a simple analytical correction:

ΔG(U) = ΔG(U = 0) - eU (6)

where U is the electrode potential on the SHE scale and e is the elementary charge.

In terms of kinetics, modelling Tafel desorption (Eq. 3) is relatively straightforward, as this non-electrochemical step can be treated using conventional reaction path methods such as the nudged elastic band (NEB) method.17-19

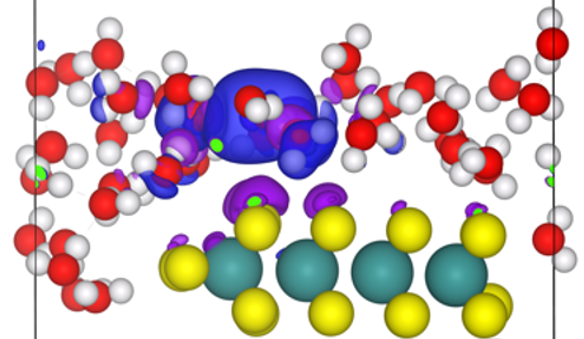

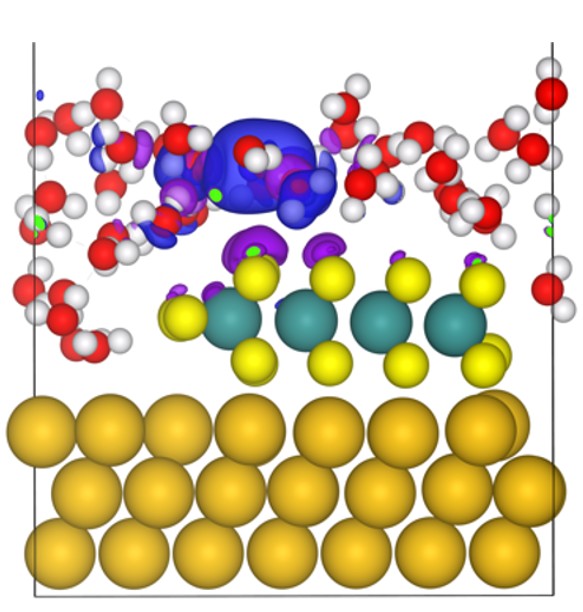

Fig. 2. H atom added to a water layer over Au(111)-supported MoS2. Isosurfaces represent charge density difference after electronic relaxation, where blue indicates a gain in positive charge and purple indicates a gain in negative charge, illustrating the formation of a solvated proton and a negatively-charged surface.

The electrochemical Volmer and Heyrovský steps present greater challenges, requiring explicit treatment of electron transfer, which precludes use of the CHE. Appropriate models must satisfy three criteria: (i) accurate representation of the solvated proton, (ii) electron energy that scales with applied potential U, and (iii) constant dipoles and electric fields during the reaction. While numerous methods are emerging,20,21 we employed the method of Skúlason et al..6,22 This method creates an electrified solid-liquid interface by constructing a water layer above the catalyst surface, equilibrating it with ab initio molecular dynamics, and introducing a neutral H atom. Upon electronic relaxation, the electron transfers to the surface, leaving a solvated proton in the water layer and negative surface charge, thereby establishing an interfacial electric field (Fig. 2). The calculated work function (ɸ) can then be related to the electrode potential:

U = ɸ - ɸSHE (7)

which can be held constant during the course of the reaction with the charge extrapolation method developed by Chan et al.23,24

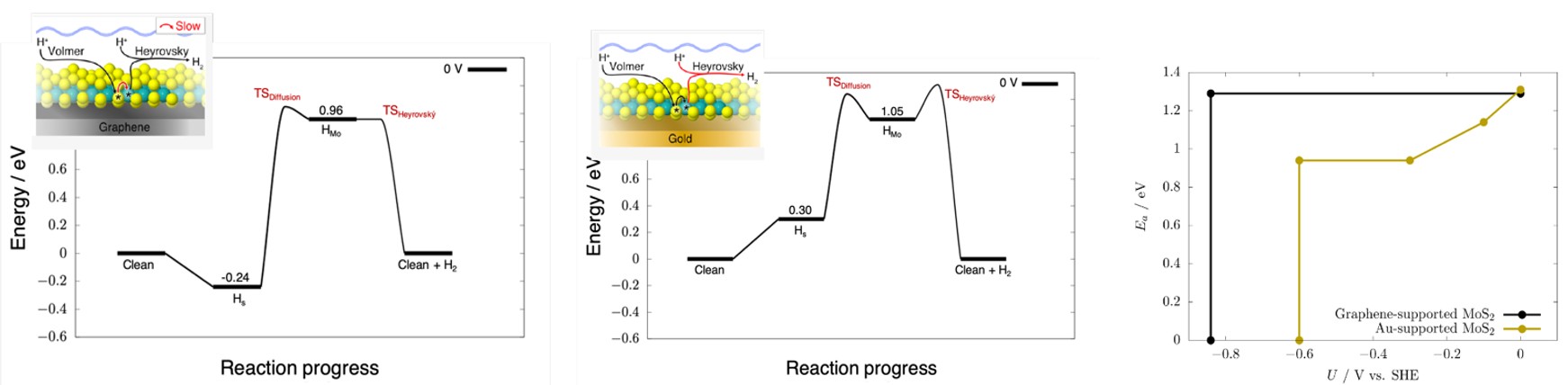

Applying this methodology to the thermodynamics and kinetics of the Volmer, Tafel, and Heyrovský steps enabled prediction of preferred mechanisms, overall reaction barriers, and current densities as functions of electrode potential for MoS2 on graphene and Au(111). Representative reaction profiles are shown in Fig. 3. The overall barriers (and thus current densities) are similar for both systems, in qualitative agreement with experiment.10,25 However, the rate-limiting steps differ between the two systems, causing them to respond differently to changing electrode potential (Fig. 3, right). This demonstrates how detailed mechanistic understanding reveals the influence of both electrode modifications (such as the Au(111) and graphene supports) and the electrochemical environment on catalytic activity.

Fig. 3. Left and centre: reaction free energy diagrams at 0 V vs SHE, for the Volmer−Heyrovský mechanism on graphene-supported MoS2 (left) and Au(111)-supported MoS2 (centre) with the electronic energy barriers between intermediates on the free energy landscape. Insets indicate the limiting process with red arrows. Right: Volmer−Heyrovský barriers as a function of potential, on graphene- and Au(111)-supported MoS2.For both supports, the potential windows in which the barrier does not change with potential are windows in which the potential-independent S-Mo diffusion barrier is limiting the overall barrier height. The Volmer−Heyrovský reaction becomes barrierless at negative potentials, due to spontaneous Volmer adsorption of Mo atoms, from which Heyrovský desorption is barrierless. Reproduced with permission from reference 15.

Electrocatalytic descriptors

While the above example demonstrates how computational modelling can elucidate mechanisms and calculate energetic barriers, calculations can also provide atomic- and electronic-scale insight into reactivity trends. This insight is essential for rational catalyst design. Ideally, such understanding can be distilled into quantitative "descriptors" that correlate directly with reaction thermodynamics or kinetics, enabling rapid catalyst screening.26 We have taken such an approach to understanding and describing the HER activity of a number of different morphologies of MoS2.

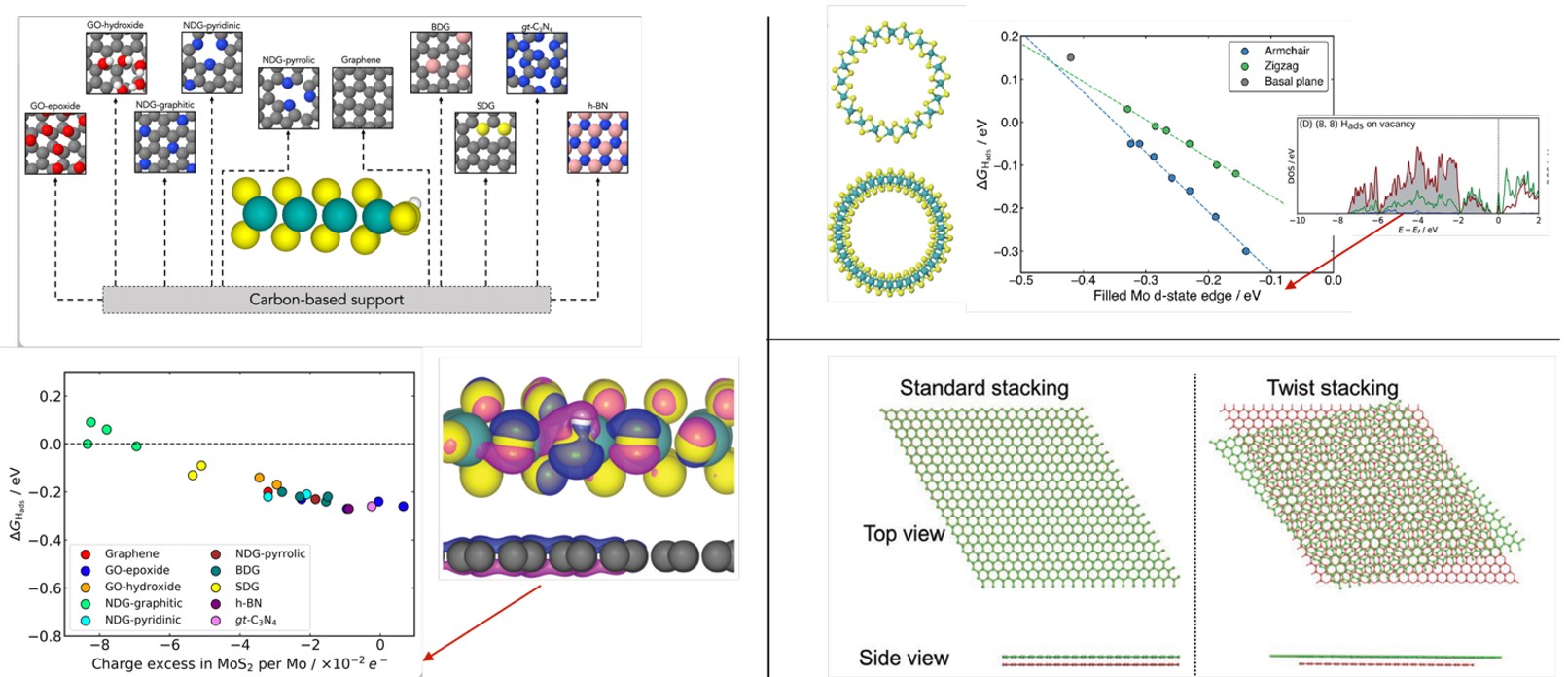

Fig. 4. Left: relation of the charge transferred to MoS2 from different support materials and Gibbs energy of H adsorption on the edge of MoS2. A distinct linear relation is observed, where supports that transfer more negative charge weaken the binding of H on the catalyst, offering precise tuning of the catalytic activity. Reproduced with permission from reference. 27. Right, top: the relation between the Mo d-state edge and Gibbs energy of H adsorption at a S-vacancy defect site across armchair and zig-zag MoS2 nanotubes of differing diameters. Reproduced from reference 28 under a CC BY-NC 3.0 license.

In a study of MoS2 on tuneable carbon-based supports, we investigated how different supports modify the activity of MoS2 basal planes and edges.27 We simplified the modelling by considering only reaction thermodynamics using the CHE, followed by electronic structure analysis of charge transfer and density of states (DOS) analysis. For 2D MoS2 basal planes on conductive supports, activity correlated with the energy of filled electronic states on the binding S atom relative to the Fermi level. This correlation arises as the binding S atom must move electron density to the lowest unoccupied state (at the Fermi level for conducting materials) in order to form the H-S bond; the energy of this transfer influences H–S binding strength. For edge sites, HER activity correlated with overall charge transfer from the supporting material to MoS2, as edge site binding is driven by charge redistribution (Fig. 4, left).

We also investigated the HER on S-vacancy defect sites on MoS2 nanotubes and found that activity correlates with surface strain imposed by curvature of the nanotube.28 We found that the curvature shifts the energy of filled d-states on Mo atoms at defect sites, thereby modulating Mo–H binding strength (Fig. 4, top right). More recently, we have begun investigating the effects of interlayer twist angle (Fig. 4, bottom right) on HER activity on supported MoS2, with initial results demonstrating tuneable catalytic activity, again linked to electronic structure modifications.29

More complex reactions

While the detailed HER modelling described previously illustrates how the electrochemical environment can be rigorously treated, more complex reactions necessitate simplified approaches. Many electrocatalytic reactions, such as CO2 reduction to hydrocarbons or alcohols,30 or formation of green ammonia31,32 involve numerous elementary steps with extensive branching pathways. Moreover, competing reactions (e.g., HER) must be considered, as protons, water, and other ions participate. For such systems, modelling typically begins with reaction thermodynamics alone, progressively adding model complexity as needed.

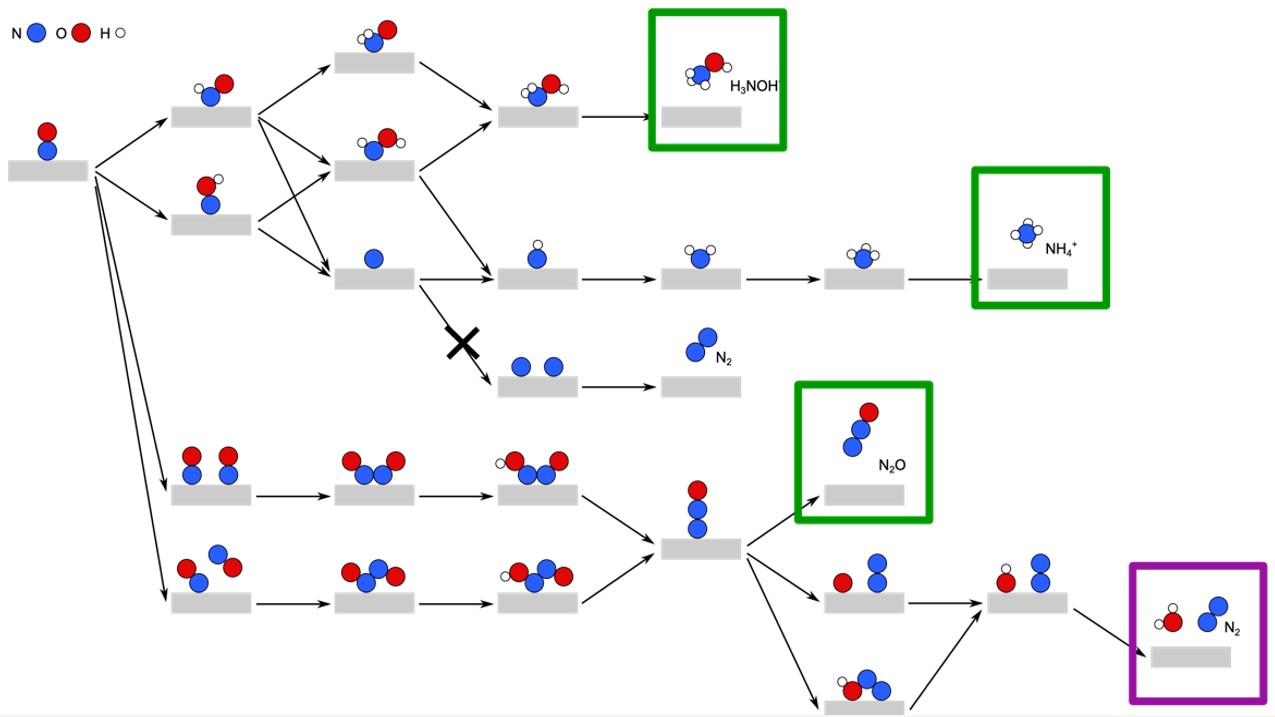

As an example from our group, we investigated the electrocatalytic reduction of NO to NH4, NH3OH, N2O and N2 on a range of transition metal surfaces.33 This reaction is important as part of electrocatalytic nitrate reduction pathways. We applied the CHE methodology to elucidate mechanisms and calculate onset potentials for each nitrogenous product. The calculated reaction network (Fig. 5) shows that CHE predicts onset potentials in good agreement with experiment for most products. However, the CHE approach proved insufficient for explaining N2 formation on certain metals. Consequently, we have undertaken more detailed modelling of this pathway, incorporating kinetic barriers and co-adsorbate effects.34 Preliminary results indicate that N2 formation is highly sensitive to co-adsorbates, highlighting the necessity of building models incrementally rather than relying on a single approach for all reactions and systems.

Fig. 5. Reaction network for the reduction of NO on transition metal electrodes, as elucidated using density functional theory calculations.33,34 Green boxes indicate products for which the onset potentials calculated using the CHE are in good agreement with experiment. The purple box indicates N2, the formation of which is not adequately described by the CHE.

Nanocatalysis

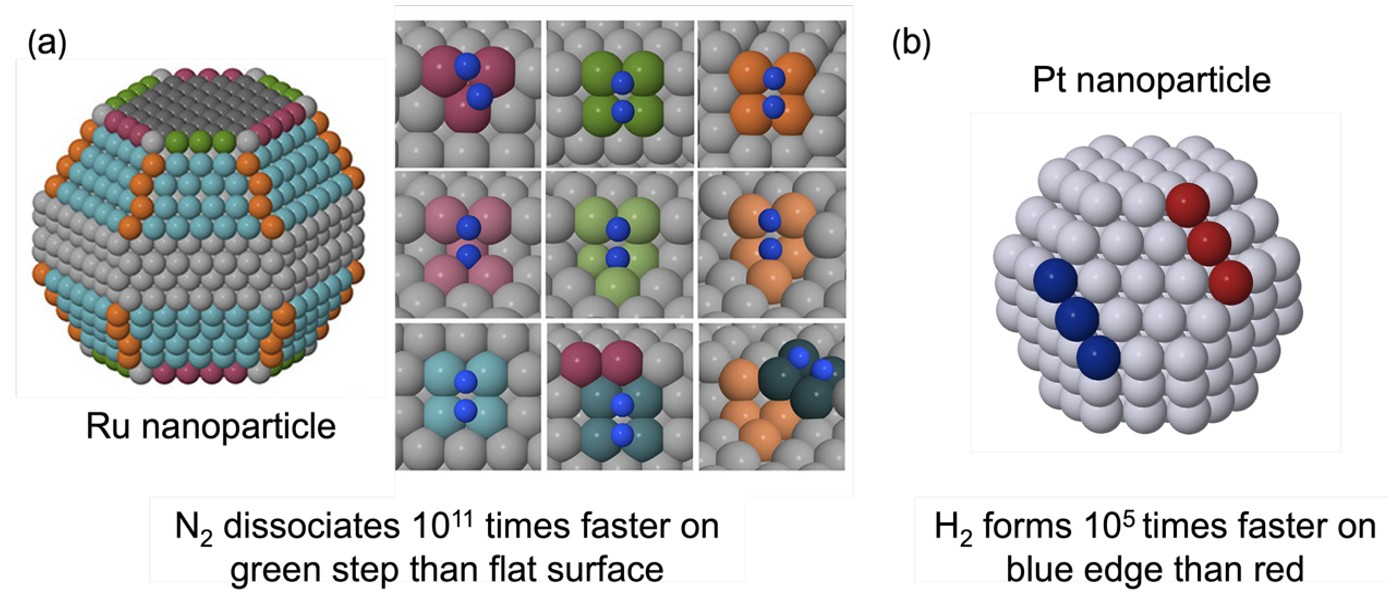

Nanoclusters (nanoparticles) are polyatomic aggregates of tens to hundreds of atoms and are finding increasing utility as heterogeneous catalysts for several reasons. Their high surface-to-bulk ratio enables equivalent catalytic activity with significantly less material than bulk catalysts, which expose only a small fraction of surface atoms. Nanoclusters may also exhibit quantum size effects, leading to properties markedly different from bulk materials. Most importantly for catalysis, nanoclusters possess abundant undercoordinated sites, edges, steps, and corners, that can dramatically enhance catalytic activity. For example, we have found that N2 dissociation on Ru nanoclusters proceeds 1011 times faster on stepped sites than planar sites (Fig. 6a).35 Furthermore, the precise atomic structure of the sites can have a large effect; we found that the rate of associative desorption of H2 from Pt nanoclusters varied by 105 times, depending on whether the edge sites are a junction between (111) and (111) surfaces, or a junction between (111) and (100) surfaces (Fig 6b).36 Clearly, to understand the catalytic activity of nanoclusters, it is imperative to first understand their structures.

Fig. 6. (a) Representative Ru nanoparticle, as well a close-up of edge and step sites stabilising the transition state of N2 dissociation. Reproduced with permission from reference 35. (b) Representative Pt nanoparticle illustrating an edge between a (100) and (111) surface (red) and a (111) and (111) surface (blue); associative desorption of H2 is 105 times faster on the (111)-(111) edge than the (100)-(111) edge.36

Global optimisation methods

Computationally determining nanocluster structure corresponds to locating the global minimum on the potential energy surface (PES), which describes the cluster energy as a function of geometry. However, cluster PESs are extraordinarily complex, even for relatively small systems. A 55-atom cluster has an estimated 1021 local minima.37 Even if evaluating each structure took (optimistically) one second, exhaustive sampling would require longer than the age of the universe. Clearly, brute force approaches are infeasible and only a subset of structures can practically be sampled. Global optimisation algorithms address this task by seeking the global minimum while visiting a tractable number of structures, typically by biasing sampling toward low-energy regions of the PES.38

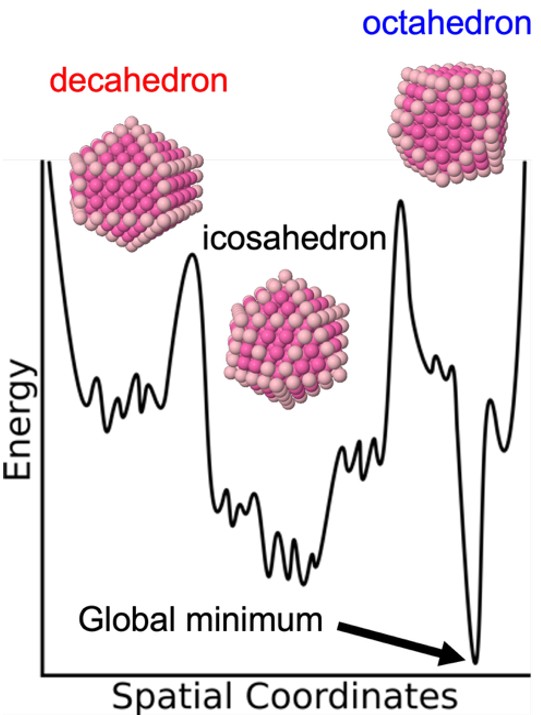

Beyond the sheer number of minima inherent to the PES of any system with many degrees of freedom, cluster PESs present an additional challenge - they often contain multiple funnels (Fig. 7) corresponding to structural variations on underlying motifs.39 Consequently, global optimisation algorithms (i) waste time resampling similar structures and (ii) may become trapped in funnels, failing to locate the global minimum. Our group’s approach addresses these issues by designing algorithms that balance the conventional bias toward low-energy structures with a drive toward structural diversity, thereby increasing PES exploration and, in principle, improving efficiency.

Fig. 7. Schematic representation of a multi-funnel potential energy surface characteristic of nanoclusters where the minima within a funnel represent small structural permutations on the overall motif (e.g. decahedron, icosahedron, octahedron) of the funnel.

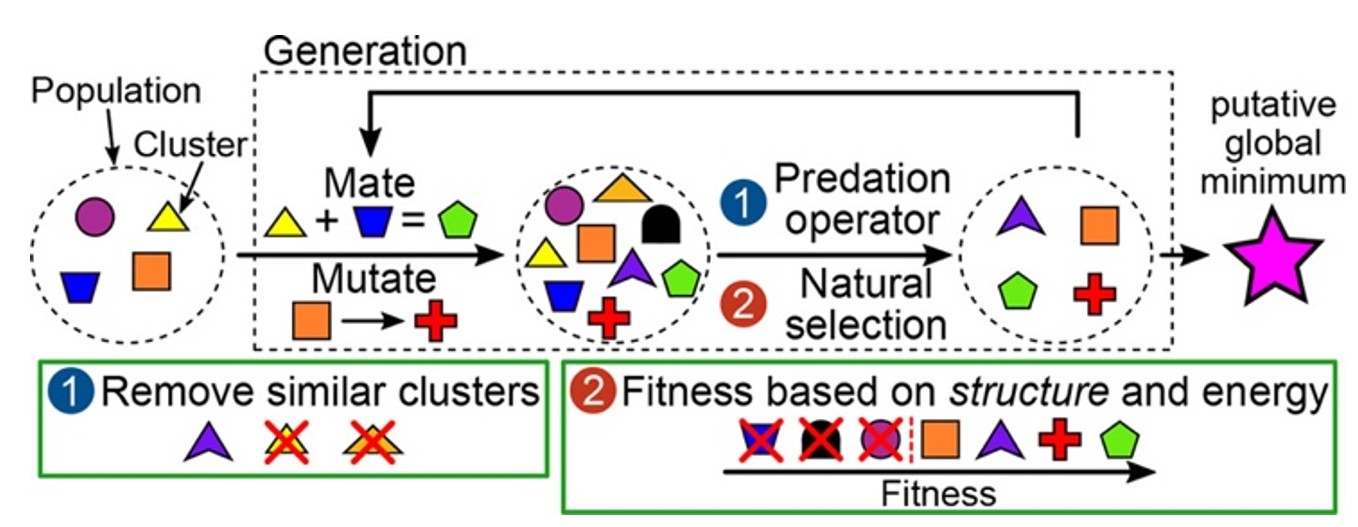

Encouraging exploration in a genetic algorithm

Our first attempt40 at improving the exploration of the nanocluster PES involved designing a modified genetic algorithm. Following Darwin's evolutionary theory, genetic algorithms maintain a "population" of cluster structures and generate new structures through "mating" (combining two clusters) and "mutation" (introducing random changes to the structure). "Natural selection" removes the least fit structures (conventionally the highest energy clusters), and the process repeats over multiple generations (Fig. 8). Our innovation was incorporating both energy and structural diversity into the fitness function - highly fit clusters are both low in energy and structurally distinct from other population members. A predation operator additionally removed structural near-duplicates.

We tested our algorithm on Lennard-Jones (LJ) clusters of various sizes. The LJ potential - a simple analytical two-body potential describing rare gas atom interactions - enables rapid energy evaluation (fractions of a second) and benefits from extensive prior PES characterisation, making it ideal for benchmarking.

Fig. 8. Schematic of the genetic algorithm. Reproduced with permission from reference 40.

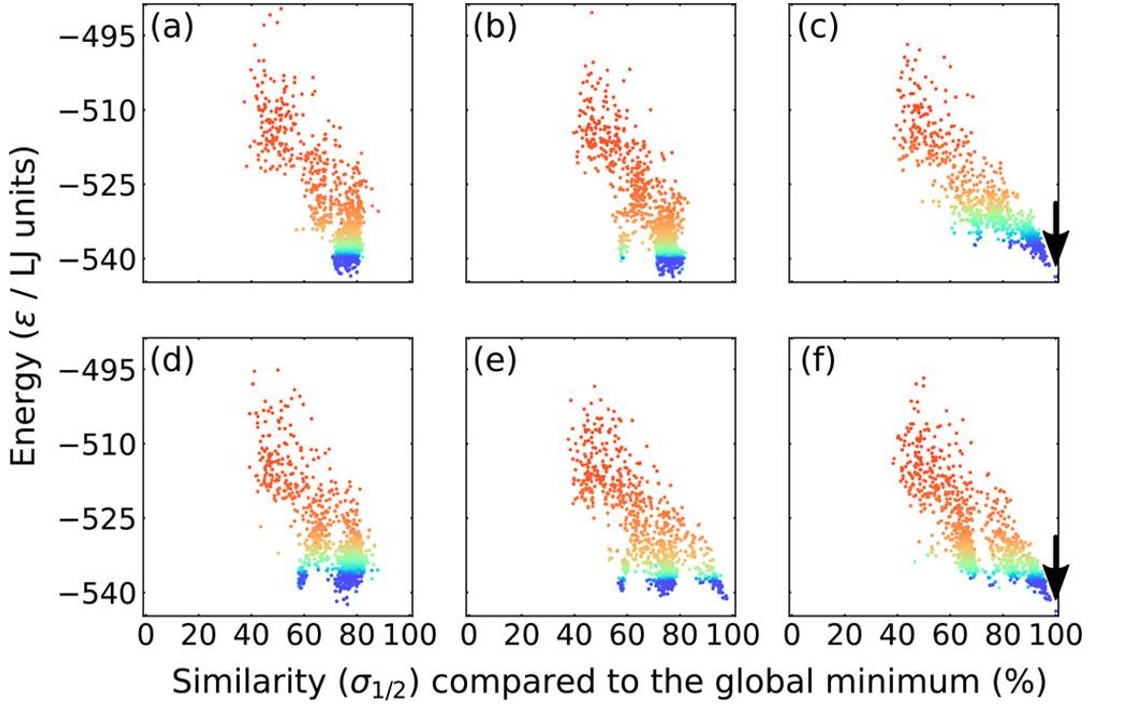

For LJ38, our algorithm outperformed conventional genetic algorithms, locating the global minimum in 1,800 ± 100 energy evaluations versus 2,600 ± 200 for the conventional energy-only fitness operator. For the more challenging LJ75, both algorithms performed comparably, requiring ~4,000,000 evaluations to locate the global minimum. Unfortunately, for LJ98 (the most difficult case), our algorithm succeeded in locating the global minimum in only 60 % of runs versus 86 % for the energy-only approach.

While disappointing, detailed PES analysis (Fig. 9) revealed that our algorithm more frequently located the correct funnel containing the global minimum but failed to reach the bottom of the funnel. This illustrates the fundamental tension between exploration and exploitation in global optimisation: broader PES exploration often directly conflicts with the drive toward low energies.

Fig. 9. Energy vs structure plots of selected LJ98 clusters encountered during a genetic algorithm implementing an energy fitness operator (a−c) or a structure + energy fitness operator (d−f). The colour of each point is associated with the generation that population was obtained. Red points are associated with earlier stages of the algorithm and blue points are associated with later stages of the algorithm. The arrow indicates the point that represents the global minimum. Reproduced with permission from reference 40.

Using memory to prevent resampling PES regions

Inspired by our first efforts at an improved global optimisation algorithm but frustrated at the lack of consistent improvements, we chose to simplify the problem by basing our next algorithm41 on the basin-hopping algorithm.42 Unlike genetic algorithms that maintain populations of clusters, basin-hopping works with single cluster structures. The algorithm perturbs a cluster's atomic coordinates semi-randomly, performs a local minimisation, then accepts or rejects this "hop" based on relative energies. Lower-energy moves are always accepted; higher-energy moves are accepted probabilistically according to the Boltzmann distribution:

This enables PES traversal via uphill moves out of funnels while still maintaining an overall low-energy bias.

Drawing on our previous work, we incorporated structural memory into basin-hopping to encourage broader PES exploration, prevent excessive resampling, and improve funnel escape. We implemented a "taboo search", maintaining a blacklist of recently visited structures. When a hop produces a structure matching the blacklist, that move is rejected and reattempted.

It should be pointed out that taboo search algorithms exist more widely in the literature, with one such algorithm designed in conjunction with the basin-hopping algorithm.42 However, these algorithms typically "reseed” (restart from a new random structure) when encountering blacklisted structures. This is inefficient; random structures are likely much higher in energy, requiring considerable effort to return to low-energy regions. Moreover, no guarantee exists against returning to the same location, which is often an entropically favoured funnel that may not contain the global minimum.

Our algorithm instead rejects blacklisted hops and attempts a different hop from the same cluster, avoiding reseed costs. We tested this on the same LJ clusters plus Au55, which presents a different PES with numerous low-lying minima and greater catalytic relevance.

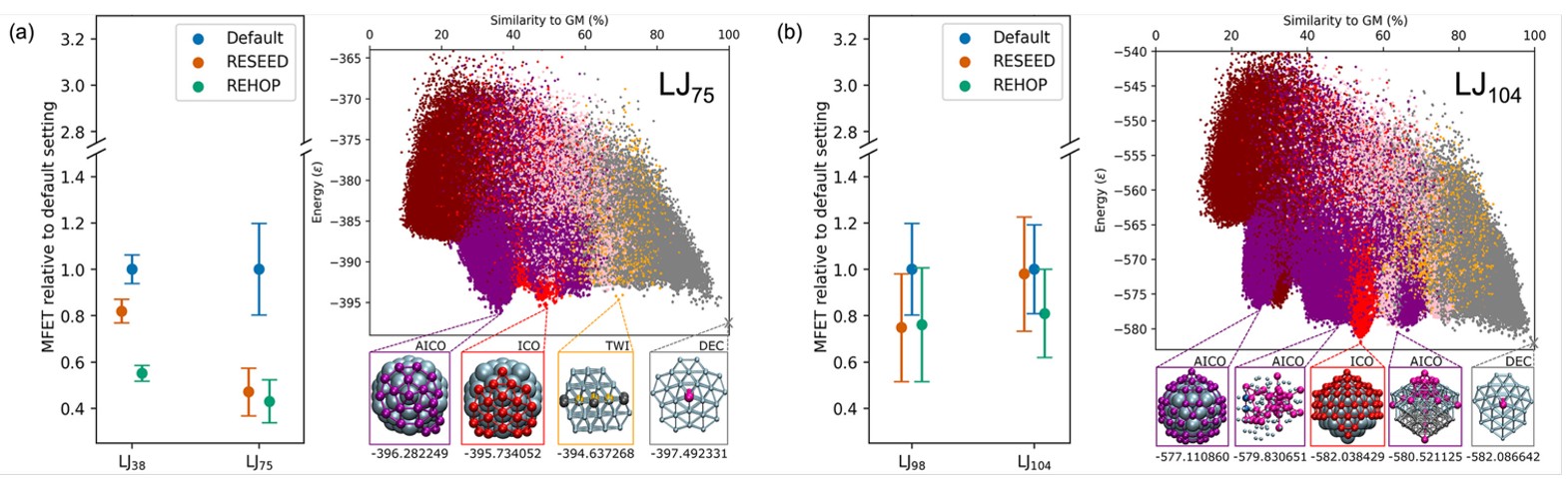

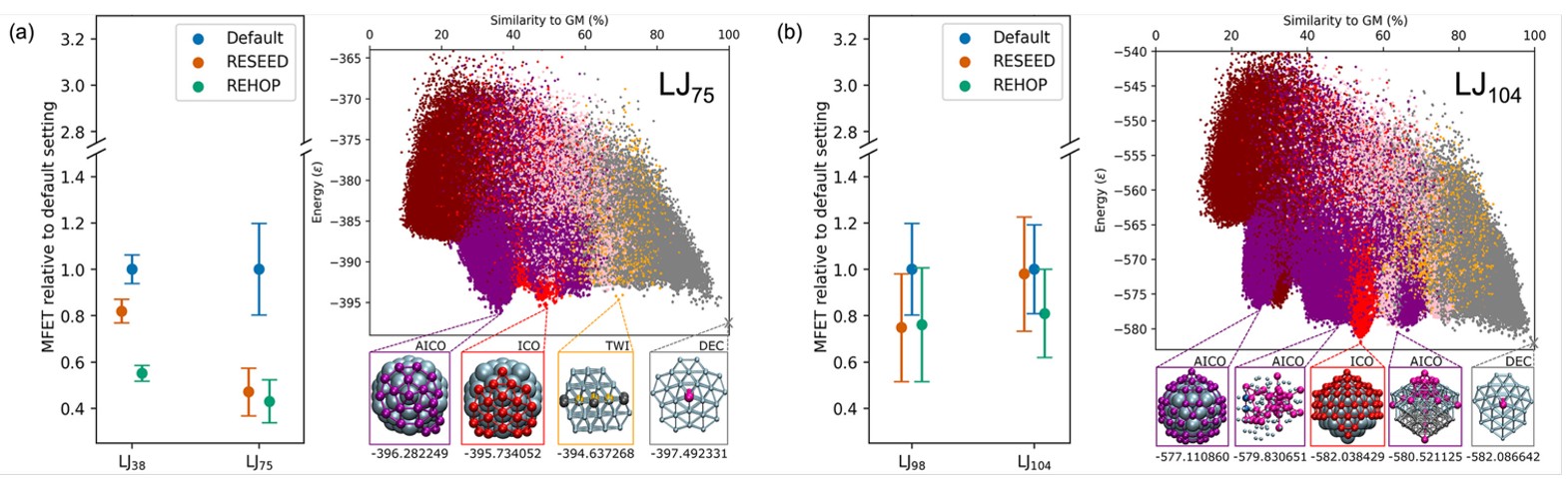

Fig. 10. Summary of best performances achieved across the double-funnel (a) and multi-funnel (b) LJ clusters PESs for the basin-hopping algorithm using: no taboo search (Default), the original taboo search implementation that triggers a reseed upon encountering the taboo region (RESEED), and the new implementation that rejects the hop into the taboo region and attempts another hop (REHOP). Also shown are energy vs structure plots that give a visual representation of the PES. Reproduced with permission from reference 41.

Both taboo search algorithms performed well for LJ clusters with double-funnel PESs (Fig. 10a). Furthermore, our "rehop" algorithm matched or exceeded the reseeding approach and proved more robust to parameter settings, inspiring greater confidence for novel systems. For clusters with more than two funnels (LJ98, LJ104, Au55), neither taboo search method showed significant improvement (Fig. 10b). Detailed analysis revealed that while our algorithm reduced time in entropically favoured funnels, it did not necessarily increase time in the global minimum's funnel, instead visiting other funnels. We conclude that a taboo search effectively prevents basin-hopping from becoming stuck in single regions of the PES but proves ineffective when multiple trapping regions exist.

These two algorithms illustrate the exploration-exploitation tension in global optimisation. While we increased exploration, this was not universally beneficial, as it often resulted in inhibited exploitation, failing to effectively reach the bottom of funnels or locating global minima.

Machine learning-assisted divide and conquer approach to global optimisation

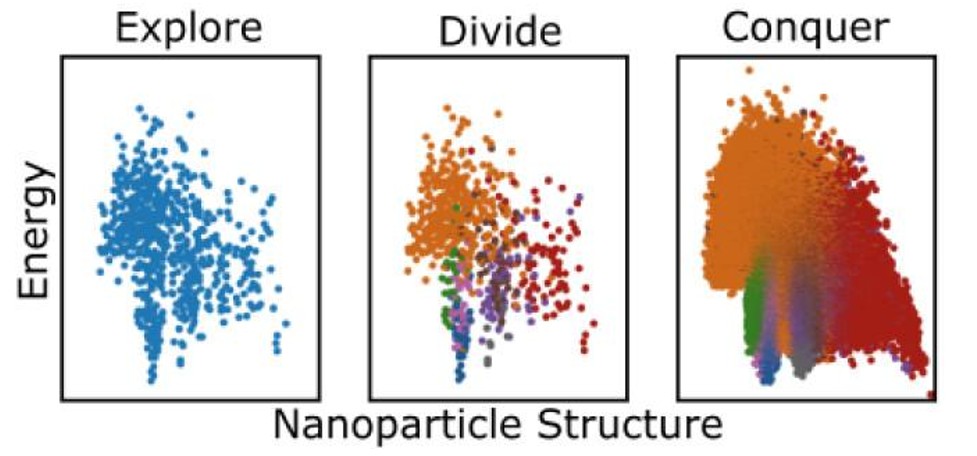

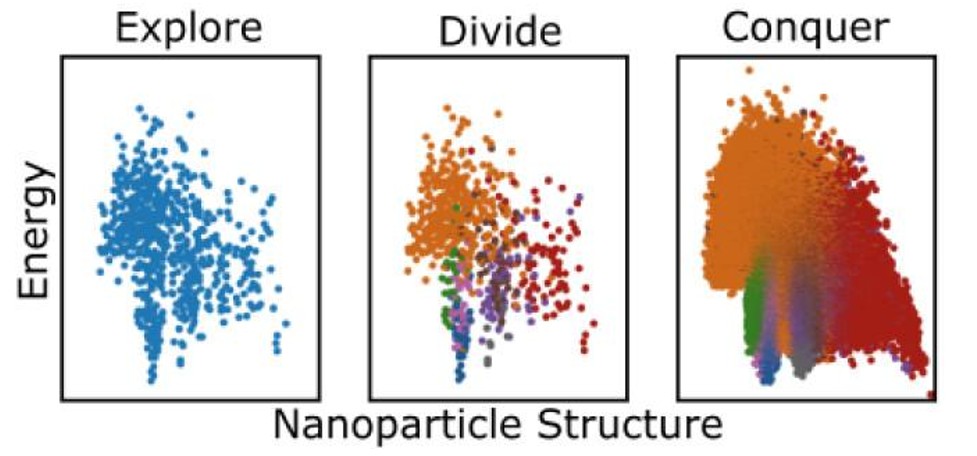

Given the difficulty balancing exploration and exploitation, our third algorithm43 took a different approach, explicitly separating exploration and exploitation phases. Inspired by computer science paradigms, we employed a divide-and-conquer approach: after brief exploration, the PES is partitioned into regions, within each of which a separate basin-hopping run is executed. This divides the complex problem into simpler sub-problems while separating problematic PES funnels encountered in our previous algorithms. Fig. 11 schematically illustrates our divide-and-conquer global optimisation algorithm (DACA).

Fig. 11. A schematic representation of the divide-and-conquer (DACA) global optimisation algorithm. In the first step, a truncated basin-hopping run is performed to obtain a broad exploration of the PES. Next, unbiased machine learning is used to cluster the structures obtained in the exploration step to define divisions of the PES. Finally, in the conquering phase, the divisions are explored in parallel, with full basin-hopping runs. Reproduced with permission from reference 43.

Literature precedent exists for divide-and-conquer algorithms in nanocluster global optimisation. Previous work showed improved performance of global optimisation of boron clusters by separately exploring planar and non-planar structures.44 Similarly, early work in our group performed "seeded" optimisation from ensembles of known low-energy structures for Au and Pt clusters of typically challenging sizes, effectively exploring different regions of the PES separately.45 While successful, these approaches rely on a priori knowledge of the PES and are unsuitable for completely unknown systems. In DACA, we employed unsupervised machine learning to partition the PES into regions in an unbiased, automated fashion. Specifically, we followed the procedure of Roncaglia and Ferrando, which represented the structure of each nanocluster as a 64-dimensional vector describing the local environments of constituent atoms.46 After partitioning, separate basin-hopping runs execute within each region, with newly generated clusters assessed by the machine learning model; hops are rejected if the resulting cluster belongs to a different PES region, thereby restricting exploitation to a specific region of the PES.

As for our other algorithms, we applied the DACA algorithm to a series of LJ clusters, Au55, as well as Pd88 in this case. An example of the PES division for LJ75 can be seen in Fig. 12a where we varied the number of divisions (k). A smaller value of k means the PES is divided into fewer, larger sections, and it therefore may take a long time to explore each section. Conversely, a higher value of k means many divisions, which may result in a less efficient algorithm, as unnecessarily large parts of the PES are explored in detail. Another setting in the basin-hopping algorithm that was varied is the temperature, kBT, with a higher temperature increasing the acceptance of higher energy moves. The performance of the DACA was assessed across these 12 settings of k and kBT and compared to the standard basin-hopping algorithm and is shown in Fig. 12b for LJ75. It can be seen that nine of the 12 settings of the DACA outperformed the conventional basin-hopping algorithm, with the best setting taking only 37 % of the time to locate the global minima.

DACA has been our best-performing global optimisation algorithm, showing improvements for LJ104, Au55, and Pd88. However, DACA again failed to efficiently locate the LJ98 global minimum. PES analysis suggests that the extremely narrow funnel containing this global minimum is difficult to identify during the DACA exploration phase and was equally challenging to locate and exploit with our previous algorithms. Indeed, the LJ98 global minimum was originally identified using a highly restrictive basin-hopping algorithm that accepted only downhill moves with frequent reseeds, representing essentially "stepwise exploitation."47

Fig. 12. (a) Energy vs similarity plot for LJ75 with the global minimum set as the similarity reference, with training data for the machine learning model plotted, and colours representing the different clusters resulting from this model at different k values. The horizontal dashed line represents the energy cutoff applied, above which data was not used for training the machine learning model. (b) Mean first encounter times of the LJ75 global minimum for the conventional basin-hopping algorithm (BHA) and the DACA at various temperatures (kBT) and clustering (k) values. Lines connecting data points are provided only to guide the eye. Reproduced with permission from reference 43.

Increased roles for machine learning

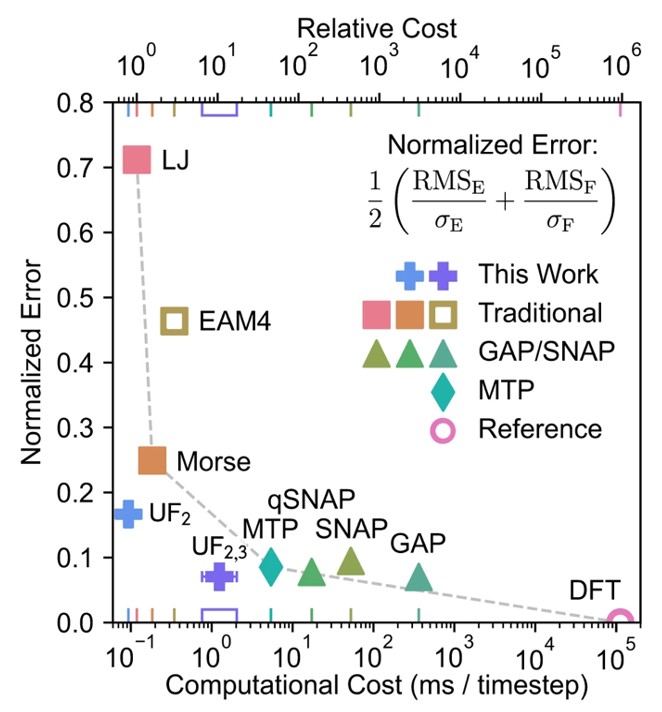

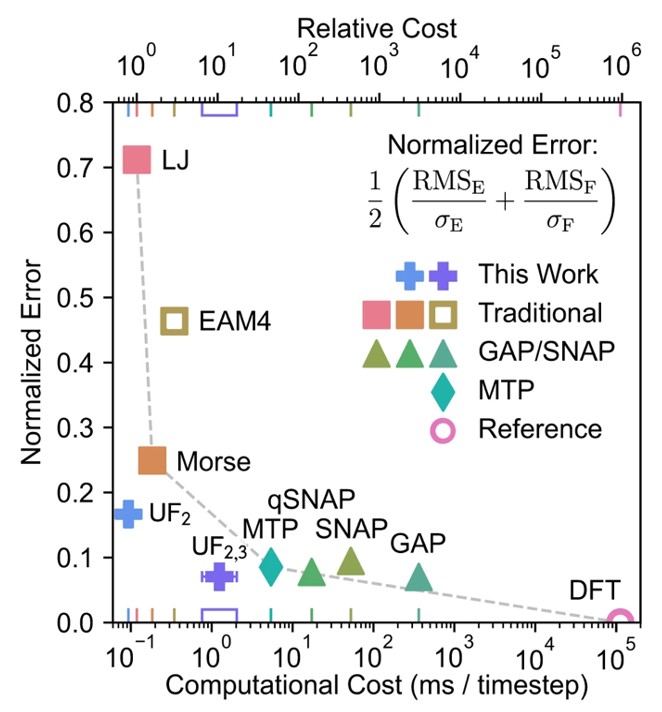

Our DACA algorithm demonstrates how machine learning can navigate and extract information from large datasets. However, machine learning offers broader applications in materials science. A particularly promising development is machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs), which dramatically reduce the computational cost for energy evaluation.48 In MLIPs, machine learning algorithms are trained on ab initio data to generate potentials with accuracy comparable to DFT but computational cost approaching empirical methods such as the Lennard-Jones and Gupta potentials described previously (Fig. 13).49,50

Fig. 13. Trade-off between prediction error and computational cost of evaluating machine-learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs). MLIPs are indicated with triangles, diamonds and crosses, empirical potentials indicated with squares. “This work” refers to reference 50. Reproduced from reference 50 under a CC BY 4.0 license.

MLIPs are especially attractive for global optimisation due to the vast number of structures evaluated during these algorithms. We have recently begun investigating MLIPs for Au cluster global optimisation using an active learning approach where the MLIP is trained "on the fly" as the PES is explored.51 We have also employed MLIPs to study dynamic structures of Au clusters, understanding not only PES minima but also thermally accessible transitions between them over time.52

Putting it all together

With our progress in both electrocatalysis and nanocatalysis, we have begun combining these fields by modelling electrocatalytic reactions on nanoclusters, the structures of which were determined using our in-house global optimisation algorithms.

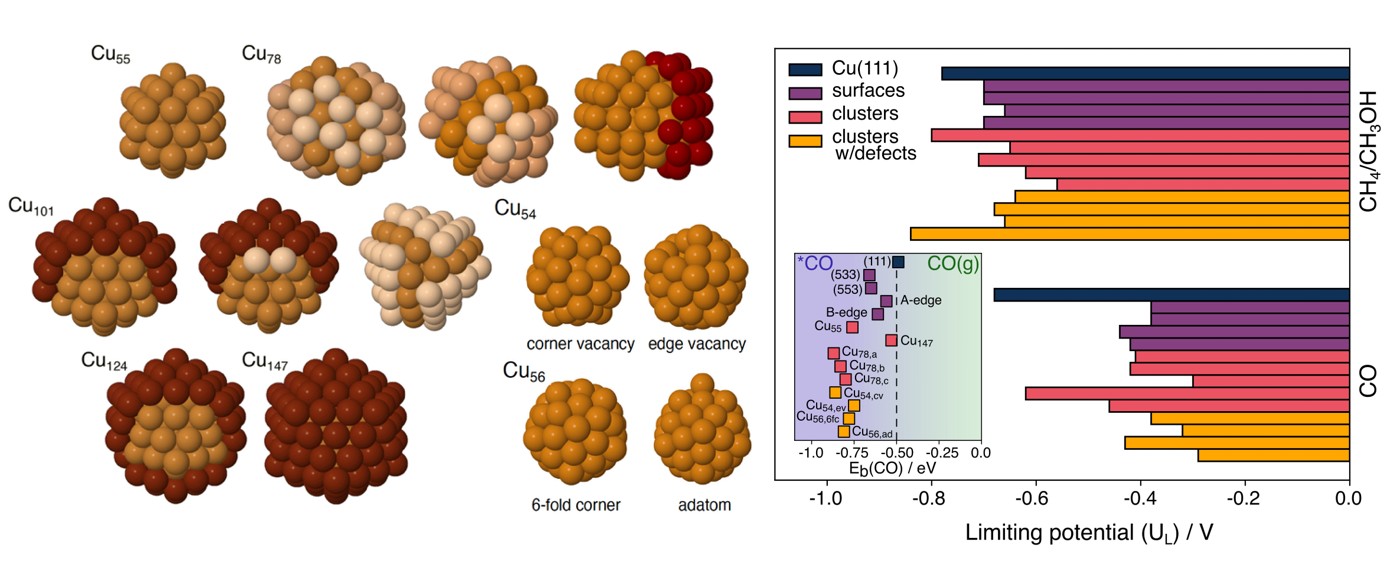

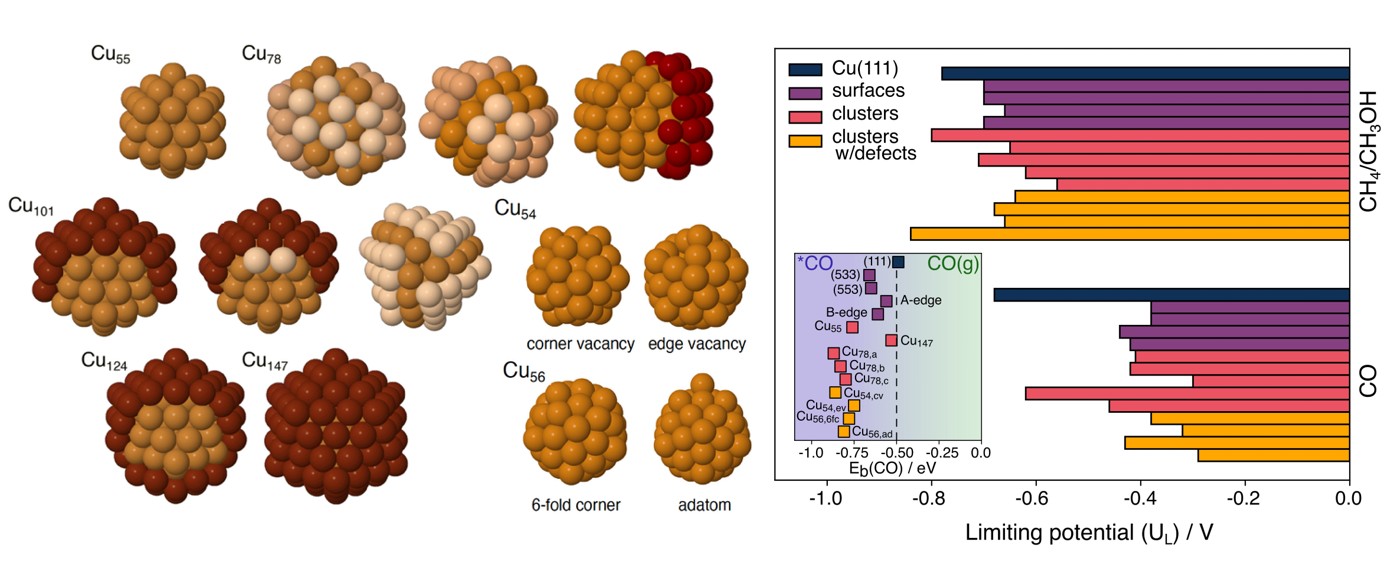

We recently studied electrocatalytic CO2 reduction to methane, methanol, and CO on Cu nanoparticles.30 Five cluster sizes were selected: Cu55, Cu78, Cu101, Cu124, and Cu147, with a mass range of ±2% considered for smaller clusters to represent typical high-precision physical syntheses.45 A range of unique structures emerged, with morphologically distinct active sites compared to those on extended bulk surfaces (Fig. 14, left). Catalytic activity varied markedly between clusters, with highly irregular 78-atom isomers yielding onset potentials for methane and methanol formation approximately 0.15 V less negative than perfect clusters (Fig. 14, right), illustrating the critical importance of atomic-scale structure in nanocatalysis.

Fig. 14. Left: Putative global minimum structures of Cu nanoclusters; (b) calculated limiting potentials (vs SHE) for the reduction of CO2 to CH4/CH3OH and CO(g) on a range of Cu catalysts. The inset indicates the calculated binding energy of CO(g), where the dashed line at Eb = 0.5 eV indicates the binding strength below which adsorbed CO is more stable than CO(g) (assuming a partial pressure of 1%) and therefore likely to reduce further to hydrogenated products. Reproduced with permission from reference 30.

Final remarks

The research described above offers insights into the challenges and opportunities in computational modelling of electro- and nanocatalysis. With the growing capabilities of machine learning, the types of materials and processes accessible by simulation will continue to expand, bringing new challenges and opportunities.

While this research describes some of our group’s work, we also have current projects in modelling materials for hydrogen storage applications,53 understanding solvation and reactions of active species in flow battery technology54 and regularly collaborate on surface chemistry problems relevant to astrochemistry.55,56 I thank the various funders (Marsden Fund, MBIE, Icelandic Research Fund, MacDiarmid Institute for Advanced Materials and Technology), computing resources (NeSI/REANNZ) as well as the financial support from the NZIC and Royal Society of Chemistry for the Easterfield tour. Most of all, I am grateful to all of my students, past and present, for their hard work and excellent company on this scientific journey!

References

- Ritter, S. K. Chem. Eng. News, 2008, 86, 53.

- Farrauto, R. J.; Heck, R. M. Catal. Today, 1999, 51, 351.

- Jasinski, R. Nature, 1964, 201, 1212.

- Boettcher, S. W. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 13095.

- Hori, Y. Electrochemical CO2 reduction on metal electrodes. In: Modern Aspects of Electrochemistry. Vayenas, C. G.; White, R. E.; Gamboa-Aldeco, M. E. Springer New York, 2008.

- Skúlason, E.; Karlberg, G. S.; Rossmeisl, J.; Bligaard, T.; Greeley, J.; Jónsson, H.; Nørskov, J. K. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2007, 9, 3241.

- Greeley, J.; Jaramillo, T. F.; Bonde, J.; Chorkendorff, I.; Nørskov, J. K. Nat. Mater. 2006, 5, 909.

- McKone, J. R.; Marinescu, S. C.; Brunschwig, B. S.; Winkler, J. R.; Gray, H. B. Chem. Sci. 2014, 5, 865.

- Jaegermann, W.; Tributsch, H. Prog. Surf. Sci. 1988, 29, 1.

- Jaramillo, T. F.; Jørgensen, K. P.; Bonde, J.; Nielsen, J. H.; Horch, S.; Chorkendorff, I. Science, 2007, 317, 100.

- Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Xie, L.; Liang, Y.; Hong, G.; Dai, H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 7296.

- Voiry, D.; Salehi, M.; Silva, R.; Fujita, T.; Chen, M.; Asefa, T.; Shenoy, V. B.; Eda, G.; Chhowalla, M. Nano Lett. 2013, 13, 6222.

- Tang, S.; Wu, W.; Zhang, S.; Ye, D.; Zhong, P.; Li, X.; Liu, L.; Li, Y.-F. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 1861.

- Tsai, C.; Abild-Pedersen, F.; Nørskov, J. K. Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 1381.

- Ruffman, C.; Gordon, C. K.; Skúlason, E.; Garden, A. L. J. Phys. Chem. C, 2020, 124, 17015.

- Nørskov, J. K.; Rossmeisl, J.; Logadottir, A.; Lindqvist, L.; Kitchin, J. R.; Bligaard, T.; Jónsson, H. J. Phys. Chem. B, 2004, 108, 17886.

- Henkelman, G.; Jónsson, H. J. Chem. Phys. 2000, 113, 9978.

- Henkelman, G.; Uberuaga, B. P.; Jónsson, H. J. Chem. Phys. 2000, 113, 9901.

- Jónsson, H.; Mills, G.; Jacobsen, K. W. Nudged Elastic Band Method for Finding Minimum Energy Paths of Transitions. In: Classical and Quantum Dynamics in Condensed Phase Simulations. World Scientific, 1998.

- Ringe, S.; Hormann, N. G.; Oberhofer, H; Reuter, K. Chem. Rev. 2021, 122, 10777.

- Melander, M. M. Current Opinion in Electrochemistry, 2021, 29, 100749.

- Skúlason, E.; Tripkovic, V.; Björketun, M. E.; Gudmundsdóttir, S.; Karlberg, G.; Rossmeisl, J.; Bligaard, T.; Jónsson, H.; Nørskov, J. K. J. Phys. Chem. C, 2010, 114, 18182.

- Chan, K.; Nørskov, J. K. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2015, 6, 2663.

- Chan, K.; Nørskov, J. K. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2016, 7, 1686.

- Bonde, J.; Moses, P. G.; Jaramillo, T. F.; Nørskov, J. K.; Chorkendorff, I. Faraday Discuss. 2009, 140, 219.

- Zhao, Z.-J.; Liu, S.; Zha, S.; Cheng, D.; Studt, F.; Henkelman, G.; Gong, J. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2019, 4, 792.

- Ruffman, C.; Gordon, C. K.; Gilmour, J. T. A.; Mackenzie, F. D.; Garden, A. L. Nanoscale, 2021, 13, 3106.

- Ruffman, C.; Gilmour, J. T. A.; Garden, A. L. Nanoscale Adv. 2021, 3, 5860.

- Prendergast, K. R.; Mills, C. S.; Garden, A. L. 2025, Manuscript in preparation.

- Weal, G. R.; Guðmundsson, K. I.; Mackenzie, F. D.; Whiting, J. R.; Smith, N. B.; Skúlason, E.; Garden, A. L. Nanoscale, 2024, 16, 5242.

- Abghoui, Y.; Garden, A. L.; Hlynsson, V. F.; Björgvinsdóttir, S.; Ólafsdóttir, H.; Skúlason, E. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 4909.

- Abghoui, Y.; Garden, A. L.; Howalt, J. G.; Vegge, T.; Skúlason, E. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 635.

- Casey-Stevens, C. A.; Ásmundsson, H.; Skúlason, E.; Garden, A. L. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 552, 149063.

- Gilmour, J. T. A.; Casey-Stevens, C. A.; Ruffman, C.; McIntyre, S. M.; Garden, A. L. 2025, Manuscript in preparation.

- Casey-Stevens, C. A.; Lambie, S. G.; Ruffman, C.; Skúlason, E.; Garden, A. L. J. Phys. Chem. C, 2019, 123, 30458.

- Skúlason, E.; Faraj, A. A.; Kristinsdóttir, L.; Hussain, J.; Garden, A. L.; Jónsson, H. Top. Catal. 2014, 57, 273.

- Doye, J. P. K; Wales, D. J. J. Chem. Phys. 1995, 102, 9659.

- Rossi, G.; Ferrando, R. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter, 2009, 21, 084208.

- Doye, J. P. K.; Miller, M. A.; Wales, D. J. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 110, 6896.

- Weal, G. R.; McIntyre, S. M.; Garden, A. L. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021, 61, 1732.

- Smith, N. B.; Jowett, T.; Yu, D.; Pahl, E.; Garden, A. L. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2023, 63, 5784.

- Wales, D. J.; Doye, J. P. K. J. Phys. Chem. A, 1997, 101, 5111.

- Smith, N. B.; Garden, A. L. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2024, 64, 8743.

- Zhao, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, J. Nano Res. 2017, 10, 3407.

- Lambie, S. G.; Weal, G. R.; Blackmore, C. E.; Palmer, R. E.; Garden, A. L. Nanoscale Adv. 2019, 1, 2416.

- Roncaglia, C.; Ferrando, R. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2023, 63, 459.

- Leary, R. H.; Doye, J. P. K. Phys. Rev. E 1999, 60, R6320.

- Behler, J. J. Chem. Phys. 2016, 145, 170901.

- Zuo, Y.; Chen, C.; Li, X.; Deng, Z.; Chen, Y.; Behler, J.; Csányi, G.; Shapeev, A. V.; Thompson, A. P.; Wood, M. A.; Ong, S. P. J. Phys. Chem. A 2020, 124, 731.

- Xie, S. R.; Rupp, M.; Hennig, R. G. npj Comput. Mater. 2023, 9, 162.

- Hay-Fourmond, E. R. F.; Garden, A. L. 2025, Manuscript in preparation.

- Hay-Fourmond, E. R. F.; Meza-González, B.; Packwood, D. P.; Garden, A. L. 2025, Manuscript in preparation.

- Dinachandran, L.; Alvares, E.; Sellschopp, K.; Klassen, T.; Jerabek, P.; Garden, A. L. Acta Mater. 2025, 301, 121514.

- Mills, C. S. Garden, A. L. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2025, https://doi.org/10.1039/D5CP03216D

- McIntyre, S. M.; Ennis, C.; Garden, A. L. ACS Earth Space Chem. 2023, 7, 1195.

- Clague, L. A.; Ennis, C.; Garden, A. L. ACS Earth Space Chem. 2024, 8, 945.

This enables PES traversal via uphill moves out of funnels while still maintaining an overall low-energy bias.

Drawing on our previous work, we incorporated structural memory into basin-hopping to encourage broader PES exploration, prevent excessive resampling, and improve funnel escape. We implemented a "taboo search", maintaining a blacklist of recently visited structures. When a hop produces a structure matching the blacklist, that move is rejected and reattempted.

It should be pointed out that taboo search algorithms exist more widely in the literature, with one such algorithm designed in conjunction with the basin-hopping algorithm.42 However, these algorithms typically "reseed” (restart from a new random structure) when encountering blacklisted structures. This is inefficient; random structures are likely much higher in energy, requiring considerable effort to return to low-energy regions. Moreover, no guarantee exists against returning to the same location, which is often an entropically favoured funnel that may not contain the global minimum.

Our algorithm instead rejects blacklisted hops and attempts a different hop from the same cluster, avoiding reseed costs. We tested this on the same LJ clusters plus Au55, which presents a different PES with numerous low-lying minima and greater catalytic relevance.

Fig. 10. Summary of best performances achieved across the double-funnel (a) and multi-funnel (b) LJ clusters PESs for the basin-hopping algorithm using: no taboo search (Default), the original taboo search implementation that triggers a reseed upon encountering the taboo region (RESEED), and the new implementation that rejects the hop into the taboo region and attempts another hop (REHOP). Also shown are energy vs structure plots that give a visual representation of the PES. Reproduced with permission from reference 41.

Both taboo search algorithms performed well for LJ clusters with double-funnel PESs (Fig. 10a). Furthermore, our "rehop" algorithm matched or exceeded the reseeding approach and proved more robust to parameter settings, inspiring greater confidence for novel systems. For clusters with more than two funnels (LJ98, LJ104, Au55), neither taboo search method showed significant improvement (Fig. 10b). Detailed analysis revealed that while our algorithm reduced time in entropically favoured funnels, it did not necessarily increase time in the global minimum's funnel, instead visiting other funnels. We conclude that a taboo search effectively prevents basin-hopping from becoming stuck in single regions of the PES but proves ineffective when multiple trapping regions exist.

These two algorithms illustrate the exploration-exploitation tension in global optimisation. While we increased exploration, this was not universally beneficial, as it often resulted in inhibited exploitation, failing to effectively reach the bottom of funnels or locating global minima.

Machine learning-assisted divide and conquer approach to global optimisation

Given the difficulty balancing exploration and exploitation, our third algorithm43 took a different approach, explicitly separating exploration and exploitation phases. Inspired by computer science paradigms, we employed a divide-and-conquer approach: after brief exploration, the PES is partitioned into regions, within each of which a separate basin-hopping run is executed. This divides the complex problem into simpler sub-problems while separating problematic PES funnels encountered in our previous algorithms. Fig. 11 schematically illustrates our divide-and-conquer global optimisation algorithm (DACA).

Fig. 11. A schematic representation of the divide-and-conquer (DACA) global optimisation algorithm. In the first step, a truncated basin-hopping run is performed to obtain a broad exploration of the PES. Next, unbiased machine learning is used to cluster the structures obtained in the exploration step to define divisions of the PES. Finally, in the conquering phase, the divisions are explored in parallel, with full basin-hopping runs. Reproduced with permission from reference 43.

Literature precedent exists for divide-and-conquer algorithms in nanocluster global optimisation. Previous work showed improved performance of global optimisation of boron clusters by separately exploring planar and non-planar structures.44 Similarly, early work in our group performed "seeded" optimisation from ensembles of known low-energy structures for Au and Pt clusters of typically challenging sizes, effectively exploring different regions of the PES separately.45 While successful, these approaches rely on a priori knowledge of the PES and are unsuitable for completely unknown systems. In DACA, we employed unsupervised machine learning to partition the PES into regions in an unbiased, automated fashion. Specifically, we followed the procedure of Roncaglia and Ferrando, which represented the structure of each nanocluster as a 64-dimensional vector describing the local environments of constituent atoms.46 After partitioning, separate basin-hopping runs execute within each region, with newly generated clusters assessed by the machine learning model; hops are rejected if the resulting cluster belongs to a different PES region, thereby restricting exploitation to a specific region of the PES.

As for our other algorithms, we applied the DACA algorithm to a series of LJ clusters, Au55, as well as Pd88 in this case. An example of the PES division for LJ75 can be seen in Fig. 12a where we varied the number of divisions (k). A smaller value of k means the PES is divided into fewer, larger sections, and it therefore may take a long time to explore each section. Conversely, a higher value of k means many divisions, which may result in a less efficient algorithm, as unnecessarily large parts of the PES are explored in detail. Another setting in the basin-hopping algorithm that was varied is the temperature, kBT, with a higher temperature increasing the acceptance of higher energy moves. The performance of the DACA was assessed across these 12 settings of k and kBT and compared to the standard basin-hopping algorithm and is shown in Fig. 12b for LJ75. It can be seen that nine of the 12 settings of the DACA outperformed the conventional basin-hopping algorithm, with the best setting taking only 37 % of the time to locate the global minima.

DACA has been our best-performing global optimisation algorithm, showing improvements for LJ104, Au55, and Pd88. However, DACA again failed to efficiently locate the LJ98 global minimum. PES analysis suggests that the extremely narrow funnel containing this global minimum is difficult to identify during the DACA exploration phase and was equally challenging to locate and exploit with our previous algorithms. Indeed, the LJ98 global minimum was originally identified using a highly restrictive basin-hopping algorithm that accepted only downhill moves with frequent reseeds, representing essentially "stepwise exploitation."47

Fig. 12. (a) Energy vs similarity plot for LJ75 with the global minimum set as the similarity reference, with training data for the machine learning model plotted, and colours representing the different clusters resulting from this model at different k values. The horizontal dashed line represents the energy cutoff applied, above which data was not used for training the machine learning model. (b) Mean first encounter times of the LJ75 global minimum for the conventional basin-hopping algorithm (BHA) and the DACA at various temperatures (kBT) and clustering (k) values. Lines connecting data points are provided only to guide the eye. Reproduced with permission from reference 43.

Increased roles for machine learning

Our DACA algorithm demonstrates how machine learning can navigate and extract information from large datasets. However, machine learning offers broader applications in materials science. A particularly promising development is machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs), which dramatically reduce the computational cost for energy evaluation.48 In MLIPs, machine learning algorithms are trained on ab initio data to generate potentials with accuracy comparable to DFT but computational cost approaching empirical methods such as the Lennard-Jones and Gupta potentials described previously (Fig. 13).49,50

Fig. 13. Trade-off between prediction error and computational cost of evaluating machine-learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs). MLIPs are indicated with triangles, diamonds and crosses, empirical potentials indicated with squares. “This work” refers to reference 50. Reproduced from reference 50 under a CC BY 4.0 license.

MLIPs are especially attractive for global optimisation due to the vast number of structures evaluated during these algorithms. We have recently begun investigating MLIPs for Au cluster global optimisation using an active learning approach where the MLIP is trained "on the fly" as the PES is explored.51 We have also employed MLIPs to study dynamic structures of Au clusters, understanding not only PES minima but also thermally accessible transitions between them over time.52

Putting it all together

With our progress in both electrocatalysis and nanocatalysis, we have begun combining these fields by modelling electrocatalytic reactions on nanoclusters, the structures of which were determined using our in-house global optimisation algorithms.

We recently studied electrocatalytic CO2 reduction to methane, methanol, and CO on Cu nanoparticles.30 Five cluster sizes were selected: Cu55, Cu78, Cu101, Cu124, and Cu147, with a mass range of ±2% considered for smaller clusters to represent typical high-precision physical syntheses.45 A range of unique structures emerged, with morphologically distinct active sites compared to those on extended bulk surfaces (Fig. 14, left). Catalytic activity varied markedly between clusters, with highly irregular 78-atom isomers yielding onset potentials for methane and methanol formation approximately 0.15 V less negative than perfect clusters (Fig. 14, right), illustrating the critical importance of atomic-scale structure in nanocatalysis.

Fig. 14. Left: Putative global minimum structures of Cu nanoclusters; (b) calculated limiting potentials (vs SHE) for the reduction of CO2 to CH4/CH3OH and CO(g) on a range of Cu catalysts. The inset indicates the calculated binding energy of CO(g), where the dashed line at Eb = 0.5 eV indicates the binding strength below which adsorbed CO is more stable than CO(g) (assuming a partial pressure of 1%) and therefore likely to reduce further to hydrogenated products. Reproduced with permission from reference 30.

Final remarks

The research described above offers insights into the challenges and opportunities in computational modelling of electro- and nanocatalysis. With the growing capabilities of machine learning, the types of materials and processes accessible by simulation will continue to expand, bringing new challenges and opportunities.

While this research describes some of our group’s work, we also have current projects in modelling materials for hydrogen storage applications,53 understanding solvation and reactions of active species in flow battery technology54 and regularly collaborate on surface chemistry problems relevant to astrochemistry.55,56 I thank the various funders (Marsden Fund, MBIE, Icelandic Research Fund, MacDiarmid Institute for Advanced Materials and Technology), computing resources (NeSI/REANNZ) as well as the financial support from the NZIC and Royal Society of Chemistry for the Easterfield tour. Most of all, I am grateful to all of my students, past and present, for their hard work and excellent company on this scientific journey!

References

- Ritter, S. K. Chem. Eng. News, 2008, 86, 53.

- Farrauto, R. J.; Heck, R. M. Catal. Today, 1999, 51, 351.

- Jasinski, R. Nature, 1964, 201, 1212.

- Boettcher, S. W. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 13095.

- Hori, Y. Electrochemical CO2 reduction on metal electrodes. In: Modern Aspects of Electrochemistry. Vayenas, C. G.; White, R. E.; Gamboa-Aldeco, M. E. Springer New York, 2008.

- Skúlason, E.; Karlberg, G. S.; Rossmeisl, J.; Bligaard, T.; Greeley, J.; Jónsson, H.; Nørskov, J. K. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2007, 9, 3241.

- Greeley, J.; Jaramillo, T. F.; Bonde, J.; Chorkendorff, I.; Nørskov, J. K. Nat. Mater. 2006, 5, 909.

- McKone, J. R.; Marinescu, S. C.; Brunschwig, B. S.; Winkler, J. R.; Gray, H. B. Chem. Sci. 2014, 5, 865.

- Jaegermann, W.; Tributsch, H. Prog. Surf. Sci. 1988, 29, 1.

- Jaramillo, T. F.; Jørgensen, K. P.; Bonde, J.; Nielsen, J. H.; Horch, S.; Chorkendorff, I. Science, 2007, 317, 100.

- Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Xie, L.; Liang, Y.; Hong, G.; Dai, H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 7296.

- Voiry, D.; Salehi, M.; Silva, R.; Fujita, T.; Chen, M.; Asefa, T.; Shenoy, V. B.; Eda, G.; Chhowalla, M. Nano Lett. 2013, 13, 6222.

- Tang, S.; Wu, W.; Zhang, S.; Ye, D.; Zhong, P.; Li, X.; Liu, L.; Li, Y.-F. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 1861.

- Tsai, C.; Abild-Pedersen, F.; Nørskov, J. K. Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 1381.

- Ruffman, C.; Gordon, C. K.; Skúlason, E.; Garden, A. L. J. Phys. Chem. C, 2020, 124, 17015.

- Nørskov, J. K.; Rossmeisl, J.; Logadottir, A.; Lindqvist, L.; Kitchin, J. R.; Bligaard, T.; Jónsson, H. J. Phys. Chem. B, 2004, 108, 17886.

- Henkelman, G.; Jónsson, H. J. Chem. Phys. 2000, 113, 9978.

- Henkelman, G.; Uberuaga, B. P.; Jónsson, H. J. Chem. Phys. 2000, 113, 9901.

- Jónsson, H.; Mills, G.; Jacobsen, K. W. Nudged Elastic Band Method for Finding Minimum Energy Paths of Transitions. In: Classical and Quantum Dynamics in Condensed Phase Simulations. World Scientific, 1998.

- Ringe, S.; Hormann, N. G.; Oberhofer, H; Reuter, K. Chem. Rev. 2021, 122, 10777.

- Melander, M. M. Current Opinion in Electrochemistry, 2021, 29, 100749.

- Skúlason, E.; Tripkovic, V.; Björketun, M. E.; Gudmundsdóttir, S.; Karlberg, G.; Rossmeisl, J.; Bligaard, T.; Jónsson, H.; Nørskov, J. K. J. Phys. Chem. C, 2010, 114, 18182.

- Chan, K.; Nørskov, J. K. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2015, 6, 2663.

- Chan, K.; Nørskov, J. K. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2016, 7, 1686.

- Bonde, J.; Moses, P. G.; Jaramillo, T. F.; Nørskov, J. K.; Chorkendorff, I. Faraday Discuss. 2009, 140, 219.

- Zhao, Z.-J.; Liu, S.; Zha, S.; Cheng, D.; Studt, F.; Henkelman, G.; Gong, J. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2019, 4, 792.

- Ruffman, C.; Gordon, C. K.; Gilmour, J. T. A.; Mackenzie, F. D.; Garden, A. L. Nanoscale, 2021, 13, 3106.

- Ruffman, C.; Gilmour, J. T. A.; Garden, A. L. Nanoscale Adv. 2021, 3, 5860.

- Prendergast, K. R.; Mills, C. S.; Garden, A. L. 2025, Manuscript in preparation.

- Weal, G. R.; Guðmundsson, K. I.; Mackenzie, F. D.; Whiting, J. R.; Smith, N. B.; Skúlason, E.; Garden, A. L. Nanoscale, 2024, 16, 5242.

- Abghoui, Y.; Garden, A. L.; Hlynsson, V. F.; Björgvinsdóttir, S.; Ólafsdóttir, H.; Skúlason, E. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 4909.

- Abghoui, Y.; Garden, A. L.; Howalt, J. G.; Vegge, T.; Skúlason, E. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 635.

- Casey-Stevens, C. A.; Ásmundsson, H.; Skúlason, E.; Garden, A. L. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 552, 149063.

- Gilmour, J. T. A.; Casey-Stevens, C. A.; Ruffman, C.; McIntyre, S. M.; Garden, A. L. 2025, Manuscript in preparation.

- Casey-Stevens, C. A.; Lambie, S. G.; Ruffman, C.; Skúlason, E.; Garden, A. L. J. Phys. Chem. C, 2019, 123, 30458.

- Skúlason, E.; Faraj, A. A.; Kristinsdóttir, L.; Hussain, J.; Garden, A. L.; Jónsson, H. Top. Catal. 2014, 57, 273.

- Doye, J. P. K; Wales, D. J. J. Chem. Phys. 1995, 102, 9659.

- Rossi, G.; Ferrando, R. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter, 2009, 21, 084208.

- Doye, J. P. K.; Miller, M. A.; Wales, D. J. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 110, 6896.

- Weal, G. R.; McIntyre, S. M.; Garden, A. L. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021, 61, 1732.

- Smith, N. B.; Jowett, T.; Yu, D.; Pahl, E.; Garden, A. L. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2023, 63, 5784.

- Wales, D. J.; Doye, J. P. K. J. Phys. Chem. A, 1997, 101, 5111.

- Smith, N. B.; Garden, A. L. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2024, 64, 8743.

- Zhao, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, J. Nano Res. 2017, 10, 3407.

- Lambie, S. G.; Weal, G. R.; Blackmore, C. E.; Palmer, R. E.; Garden, A. L. Nanoscale Adv. 2019, 1, 2416.

- Roncaglia, C.; Ferrando, R. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2023, 63, 459.

- Leary, R. H.; Doye, J. P. K. Phys. Rev. E 1999, 60, R6320.

- Behler, J. J. Chem. Phys. 2016, 145, 170901.

- Zuo, Y.; Chen, C.; Li, X.; Deng, Z.; Chen, Y.; Behler, J.; Csányi, G.; Shapeev, A. V.; Thompson, A. P.; Wood, M. A.; Ong, S. P. J. Phys. Chem. A 2020, 124, 731.

- Xie, S. R.; Rupp, M.; Hennig, R. G. npj Comput. Mater. 2023, 9, 162.

- Hay-Fourmond, E. R. F.; Garden, A. L. 2025, Manuscript in preparation.

- Hay-Fourmond, E. R. F.; Meza-González, B.; Packwood, D. P.; Garden, A. L. 2025, Manuscript in preparation.

- Dinachandran, L.; Alvares, E.; Sellschopp, K.; Klassen, T.; Jerabek, P.; Garden, A. L. Acta Mater. 2025, 301, 121514.

- Mills, C. S. Garden, A. L. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2025, https://doi.org/10.1039/D5CP03216D

- McIntyre, S. M.; Ennis, C.; Garden, A. L. ACS Earth Space Chem. 2023, 7, 1195.

- Clague, L. A.; Ennis, C.; Garden, A. L. ACS Earth Space Chem. 2024, 8, 945.