Introduction

Some organic molecules can arrange neatly together, leaving behind tiny gaps or spaces that act like microscopic sponges for gases. These spaces can trap and store molecules such as carbon dioxide, methane, or even harmful vapors, providing creative solutions to some of today’s pressing environmental problems. By making small changes to their molecular structures, chemists can control how these molecules stack or fit together and, in turn, how selectively they capture gas. This approach shows how the world of chemistry can make a real difference to one of today’s biggest problems, climate change. Organic chemistry, in this way, has become a tool not just for discovery of new molecules but for building a more sustainable future.

When designed as porous frameworks, organic molecules become especially powerful. Their high surface areas, tunable pore sizes, and versatile chemical functionalities give them the flexibility to capture a wide variety of gases. From reducing greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4), to filtering toxic industrial pollutants such as sulfur dioxide (SO2) and ammonia (NH3), these materials function as selective molecular sponges, absorbing what we want to remove and, in many cases, releasing it again when needed.

Among porous materials, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) have set the standard in recent years. Built from metal centres connected by organic linkers, MOFs are well known for their extremely high surface areas and highly tunable structures. They have shown impressive performance in capturing CO2, storing hydrogen, and even harvesting water from the atmosphere. While MOFs remain a cornerstone of porous material research, this article turns its attention to fully organic systems. These materials, free from metal components, bring their own advantages of lighter weight, superior stability, versatile chemical functionality, and in many cases greater accessibility from renewable sources. Together, they extend the potential of MOFs while opening new pathways for sustainable gas capture.1

Several families of porous organic materials illustrate this versatility. Porous organic polymers (POPs) are lightweight, chemically stable, and relatively inexpensive to synthesise, making them attractive candidates for large scale applications.2 Covalent organic frameworks (COFs) offer a more ordered approach, their crystal structures allow chemists to fine-tune pore size and chemistry at the molecular level.3 Porous organic cages, on the other hand, are discrete, and can be designed to trap specific gases, often with the added benefit of being soluble and easy to process.4 Furthermore, hydrogen bonded organic frameworks (HOFs) have emerged, using the directionality of hydrogen bonds to assemble into porous architectures which show promising selectivity for gases like CO2, CH4 and hydrocarbons.5

One of the most exciting directions in this field is making porous materials from natural, renewable resources. A good example is lignin, a substance found in plants and produced in large amounts as waste from the paper and biofuel industries. Instead of being discarded, lignin can be transformed into porous carbons, a lightweight material with extremely large internal surface areas that act like sponges for gases. Because these carbons come from renewable plant-based feedstocks, they not only perform well in capturing gases but also support a more sustainable approach to material design. This is because plant-derived products naturally contain oxygen, nitrogen-rich and aromatic structures that can be converted into porous frameworks ideal for gas adsorption.6

Another fascinating class of porous materials are the membrane-based polymers of intrinsic microporosity (PIMs). These polymers are built from rigid and twisted backbones that cannot pack together efficiently. The result is that permanent gaps, or micropores, are locked into their structure. These pores, usually smaller than two nanometers, give PIMs very high surface areas and allow them to adsorb large amounts of gases with remarkable efficiency.7

Across all these systems, porosity is the key feature. Micropores, those smaller than two nanometers, are especially effective at trapping small gas molecules through physical interactions. To increase selectivity, chemists can also introduce functional groups like amines, hydroxyls, or carboxyl, which provide sites for reversible chemical interactions. The result is a balance between strong enough binding to capture gases efficiently, yet weak enough to allow easy release and reuse of the material.8

In this article, we take a panoramic view of porous organic molecular sponges; how they are designed, how they capture gases, and why they represent a promising pathway toward cleaner air and safer environments.

Gas capture in porous organic materials

Porosity alone does not guarantee efficient gas capture. The chemistry of the framework and the way trapped gases interact with molecules are equally important. Different organic porous materials rely on different strategies, from simple physical entrapment to specific chemical binding.

Gas capture by porous organic polymers (POPs)

POPs are one of the most versatile families of gas adsorbing materials, being lightweight, stable networks built from entirely organic components. Their permanent porosity, large internal surface area, and tunable structures make them excellent hosts for capturing greenhouse gases or industrial contaminants. Moreover, their chemistry can be tailored by inserting functional groups (e.g. amines, pyridine units) to enhance selectivity or even create active sites for gas conversion.

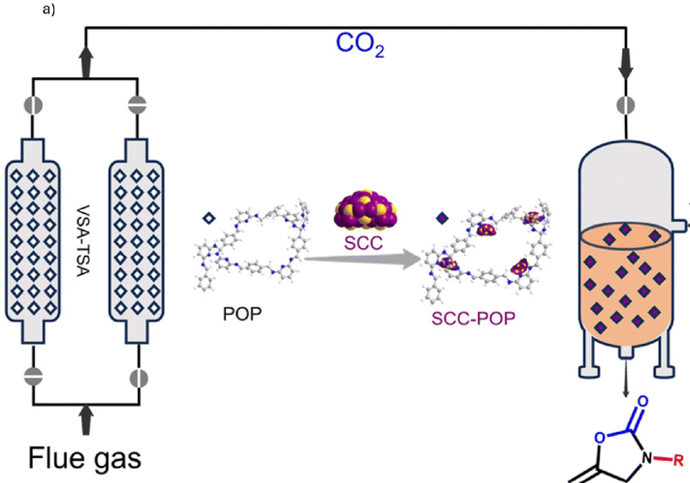

Pyridine-functionalised POPs for CO2 capture & catalysis

Researchers designed pyridine-rich POPs that act both as efficient CO2 sorbents and support for catalytic silver chalcogenolate clusters (SCC) - nanoclusters composed of silver and chalcogenolate ligands, where chalcogenolates are sulfur, selenium or tellurium containing compounds that convert captured CO2 into useful products (Fig. 1). In continuous test setups simulating flue gas, these materials demonstrated strong gas capture capability, handling around 20 L of flue gas per kilogram of POP per hour and facilitated catalytic conversion in flow systems. The CO2 adsorption and regeneration processes were carried out under vacuum swing adsorption (VSA) and temperature swing adsorption (TSA) conditions. This dual-function behavior makes them promising for efficient carbon capture and utilisation.9

Fig. 1. a) Continuous capture of CO2 from flue gas and its direct conversion into fine chemicals; b) structures of pyridine-rich POPs. Reproduced with permission from reference 9.

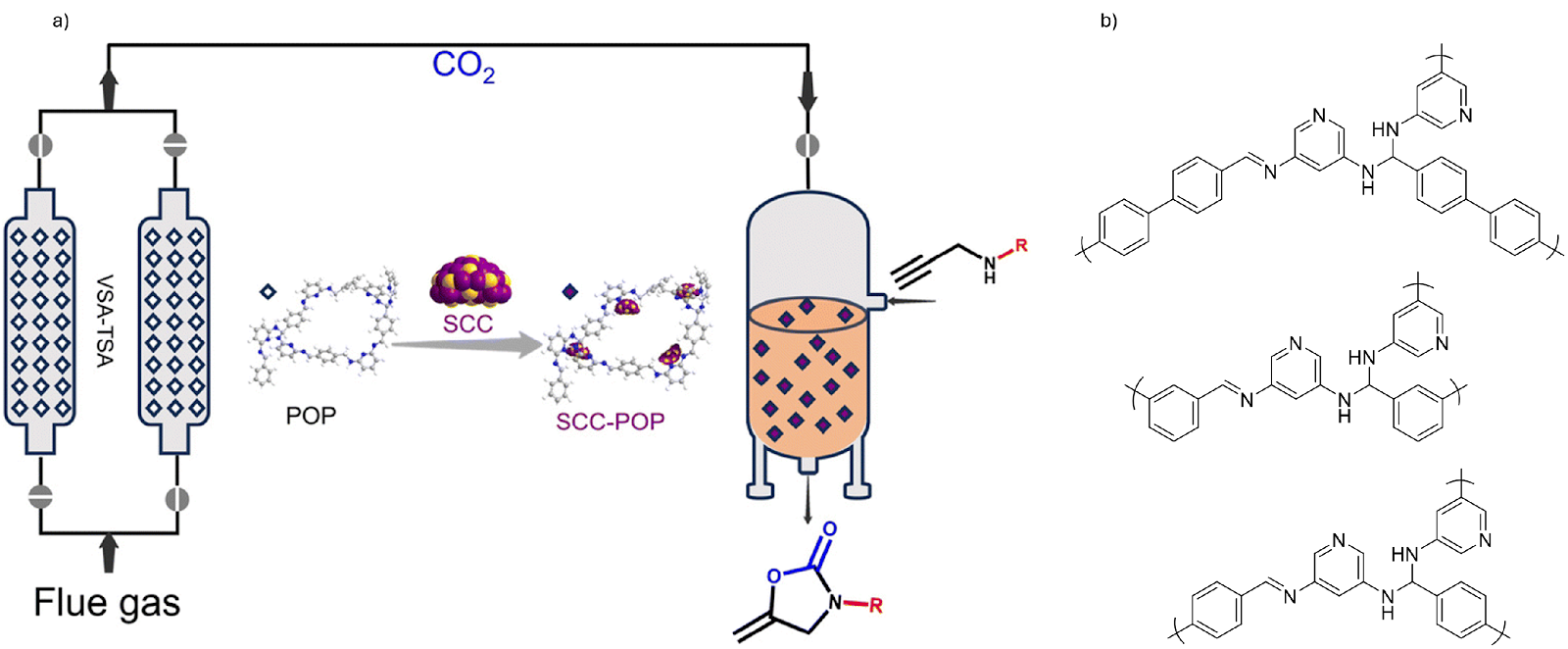

Porphyrin-based nanoporous POPs for mixed gas adsorption

Porphyrin-based nanoporous organic polymers (PNOPs) are emerging as promising molecular sponges for selective gas capture (Fig. 2). Recently, three-dimensional PNOP networks were synthesised using tetrahedral building blocks, giving materials with high surface areas (up to 830 m2g-1) and less than 2 nm pores. These PNOPs showed a remarkable uptake of CO2 (up to 160 mg per g at 273 K, 1 bar) along with ethane and methane. Moreover, structural changes allowed control over pore size and selectivity, highlighting their potential for efficient greenhouse gas separation and storage.10

Fig. 2. a) One pot synthesis of porphyrin-based nanoporous organic polymers (PNOP-1 & PNOP-2); b) gas adsorption performance of PNOP-1. Adsorption isotherms at 273 K show CO2 (red), ethane (black), and methane (blue) uptake, with PNOP-1 indicating high CO2 capacity. Reproduced with permission from reference 10.

Gas capture by covalent organic frameworks (COFs)

The development of COFs for gas capture can be seen as a stepwise evolution, beginning with structures that mainly provided open space for gases, and advancing toward frameworks designed with specific chemistry to enable stronger and more selective interactions.

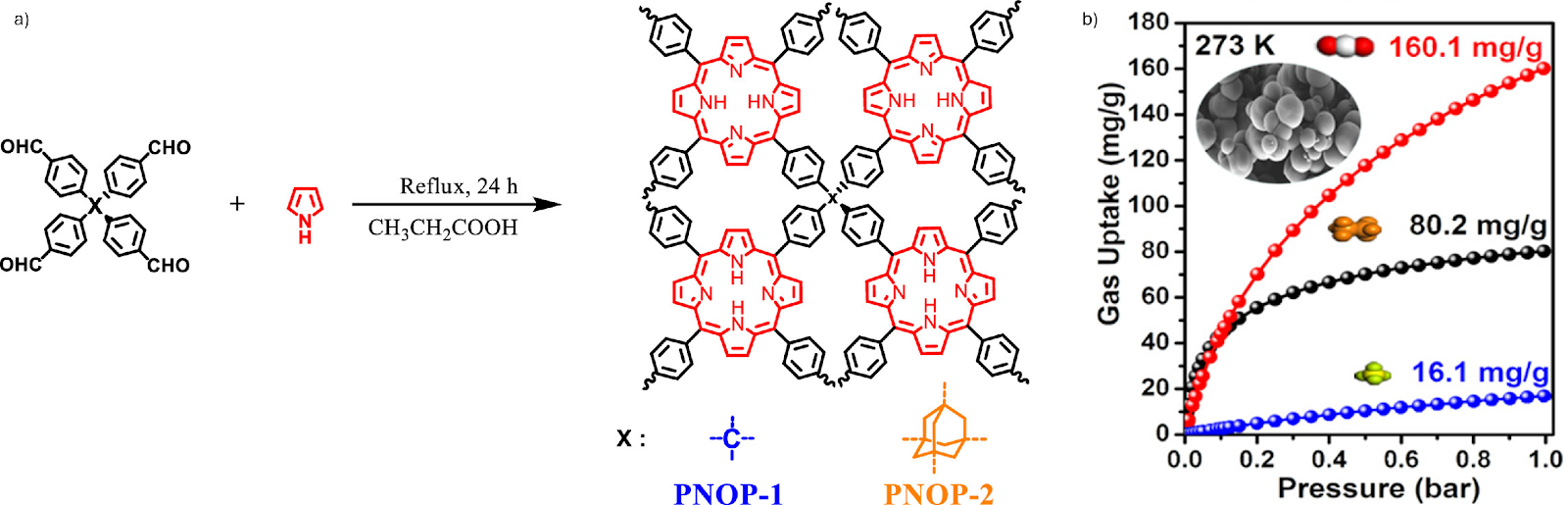

COF-102/103 for high-pressure CO2 storage

One of the earliest examples of COFs for gas capture were reported by Yaghi and co-workers, who constructed a family of boronate-ester COFs from simple building blocks such as hexahydroxytriphenylene (HHTP) and various boronic acids. As shown in Fig. 3, condensation reaction of these components led to frameworks with different pore sizes and connectivities. What made these structures remarkable was their crystallinity and the extremely low densities they achieved while still offering large, accessible pores.

The CO2 adsorption studies of these COFs show that frameworks with larger pore volumes, like COF-102 and COF-103, could hold significantly more CO2 at high pressures than smaller-pore COFs. The uptake in COF-102 reached over 1000 mg g-1 at 50 bar, among the highest values reported for purely organic porous materials at that time. Importantly, the storage is governed by physisorption which is weak van der Waals interactions between the gas molecules and the extended aromatic pore walls.11

Fig. 3. Synthesis of COFs from boronic acids and HHTP. Shown is representative 2D frameworks (COF-1, -5, -6, -8, -10) and 3D frameworks (COF-102, -103). Reproduced with permission from reference 11.

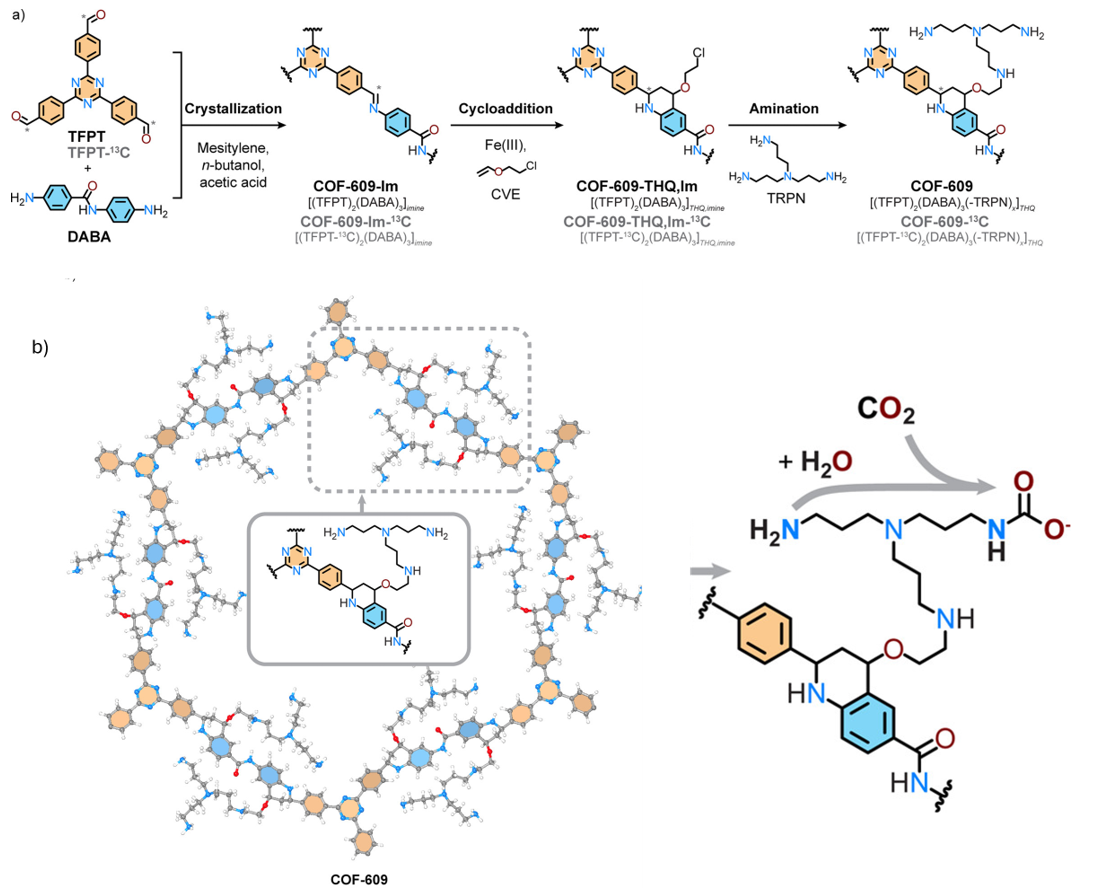

Amine-functionalised COF-609

A good example of how chemistry inside the pores can change gas capture is seen in COF-609 (Fig. 4). The framework was first built through imine condensation, then stabilised by converting those linkages into more robust tetrahydroquinoline units. The crystallinity and stability of these steps were confirmed by PXRD patterns. In a further step, amine groups were introduced into the pores, creating well defined sites for CO2 binding. This design is reflected in the adsorption capacity, where COF-609 shows a steep uptake even at very low pressures, close to the levels of CO2 in ambient air. Importantly, the capture does not rely only on weak physisorption; the amines interact chemically with CO2, and the presence of water improves the process. This combination of rational synthesis, strong uptake, and a clear capture mechanism highlights how COFs can move beyond passive storage to become truly active sorbent materials.12

Fig. 4. a) Synthetic route showing imine-based COF transformed into tetrahydroquinoline-linked COF-609; b) crystal arrangement of COF-609 & illustration of CO2 capture mechanism. Reproduced with permission from reference 12.

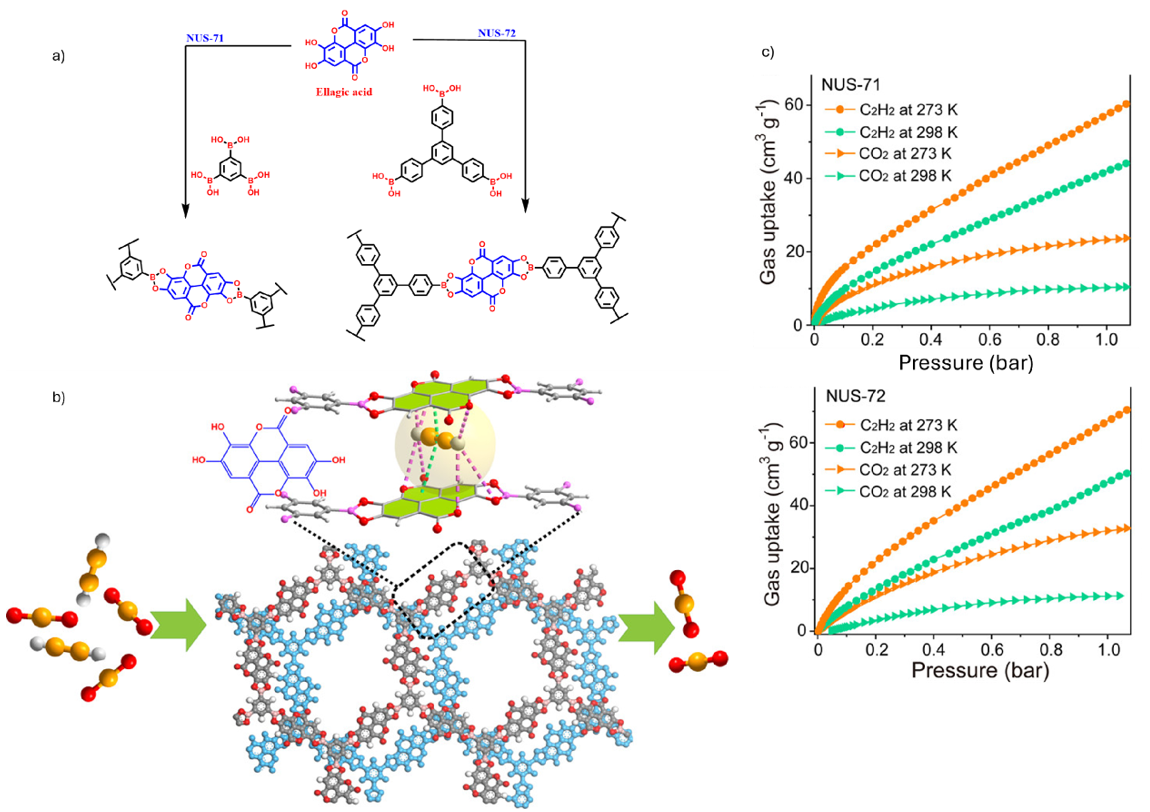

NUS-71 & NUS-72 for preferential acetylene adsorption

Not all gas capture efforts in COFs are about CO2. An interesting example is illustrated by NUS-71 and NUS-72. NUS-71 and NUS-72 were constructed from ellagic acid, a naturally occurring polyphenol condensed with boronic acid linkers (Fig. 5a). The resulting frameworks are ultra microporous and give well defined pore interiors lined with hydrogen-bonding groups.13

The adsorption mechanism is highlighted in Fig. 5b, where acetylene molecules can engage in multiple CH-O and π-π interactions with the pore walls. These directional interactions give acetylene a thermodynamic advantage over CO2, which cannot establish the same strength of binding. This effect is clearly seen in the gas uptake data Fig. 5c, where both NUS-71 and NUS-72 exhibit significantly higher adsorption capacities for C2H2 compared to CO2 at ambient conditions, with sharp uptakes at low pressures.

Together, these results show how careful selection of linkers and pore chemistry, even from natural feedstocks, can deliver highly selective COFs for challenging gas separations such as C2H2/CO2.13

Fig. 5. a) Synthetic scheme showing construction of COFs (NUS-71 & NUS-72) from ellagic acid and boronic acid linkers; b) schematic representation of pore environments and preferential acetylene binding via multiple non-covalent interactions; c) gas adsorption isotherms at 273 K & 298 K demonstrating selective uptake of C2H2 over CO2. Reproduced with permission from reference 13.

Overall, these examples show how COFs can be designed for gas capture by carefully adjusting their linkers, pore structures, and chemical functionalities. By improving stability, adding reactive binding sites, or fine-tuning pore environments, COFs demonstrate both structural adaptability and strong potential for meeting different gas separation needs.

Gas capture by porous organic cages (POCs)

Another important group of porous materials for gas capture is porous organic cages (POCs). Unlike COFs, which form extended two or three-dimensional covalent frameworks, POCs are discrete molecular units that contain internal cavities and permanent porosity. Their modular synthesis allows precise control over size, shape, and functionality, while their solubility in common solvents offers processing advantages that framework materials often lack. These characteristics make POCs a complementary platform to COFs, where molecular precision and solution processability are important.

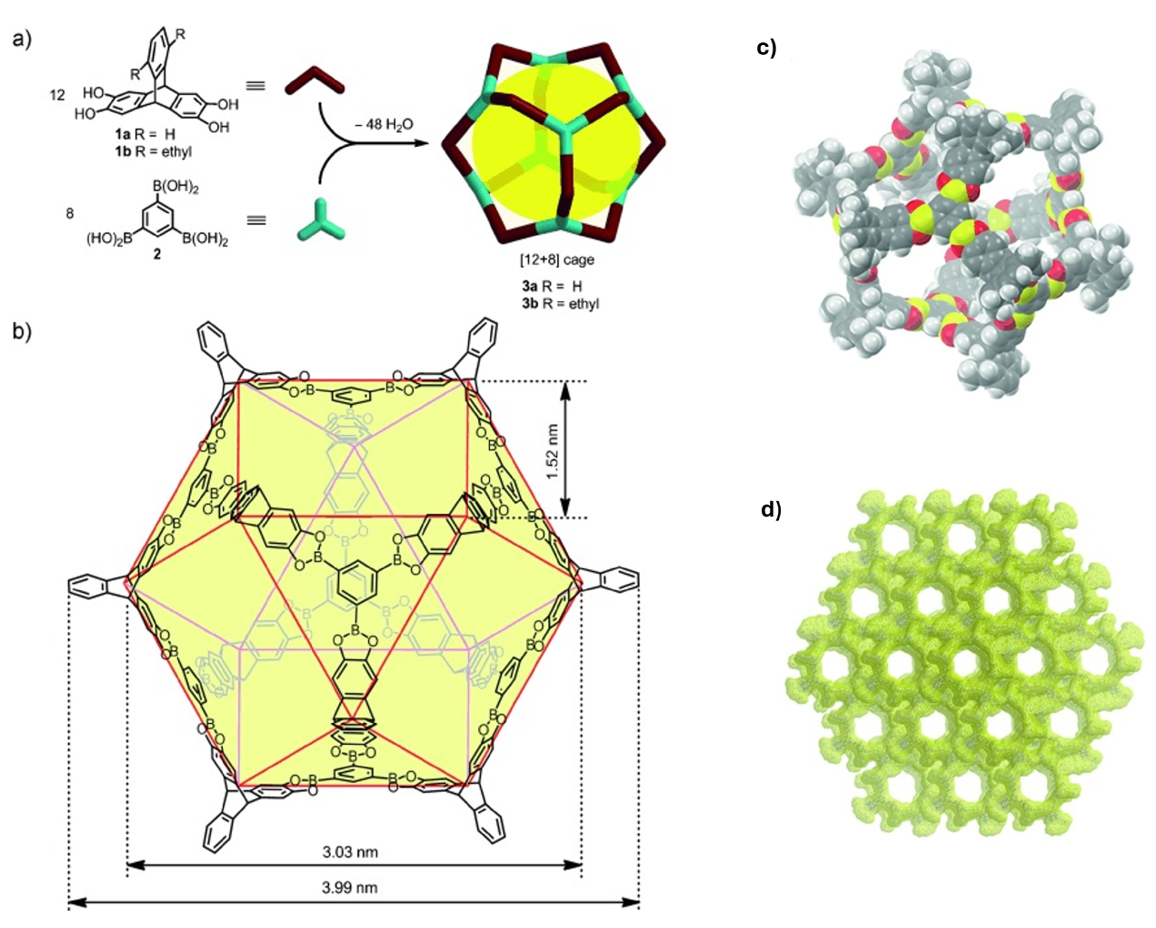

Molecular design of a mesoporous organic cage

In 2014, Zang and colleagues reported a permanent mesoporous organic cage that represented a milestone in the development of molecular porous materials. The cage was obtained by one step 48-fold condensation reaction of twelve molecules of triptycene tetraol with eight molecules of the triboronic acid to the cuboctahedral [12+8] cages affording a discrete molecule with a rigid and open framework (Fig. 6). The single-crystal structure highlights its well-defined cavities and interconnected channels, which contribute to the high porosity of the material. Nitrogen adsorption experiments further confirmed the permanent and accessible nature of these pores. This work established that porous organic cages can be engineered not only for microporosity but also to achieve mesoporous domains, showcasing their potential applications in gas storage and molecular separation.14

Fig. 6. a) One-step 48-fold condensation reaction of twelve molecules of triptycene tetraol 1 a or 1 b with eight molecules of the triboronic acid 2 to the cuboctahedral [12+8] cages 3a and 3b, respectively; b) the scaffold of the cuboctahedral cage, edges of the cuboctahedral geometry are highlighted in red; c) space-filling model, C gray, H white, O red, B yellow; d) packing in the solid state, yellow surface represents a solvent accessible surface with a probe radius of 1.8 Å. Reproduced with permission from reference 14.

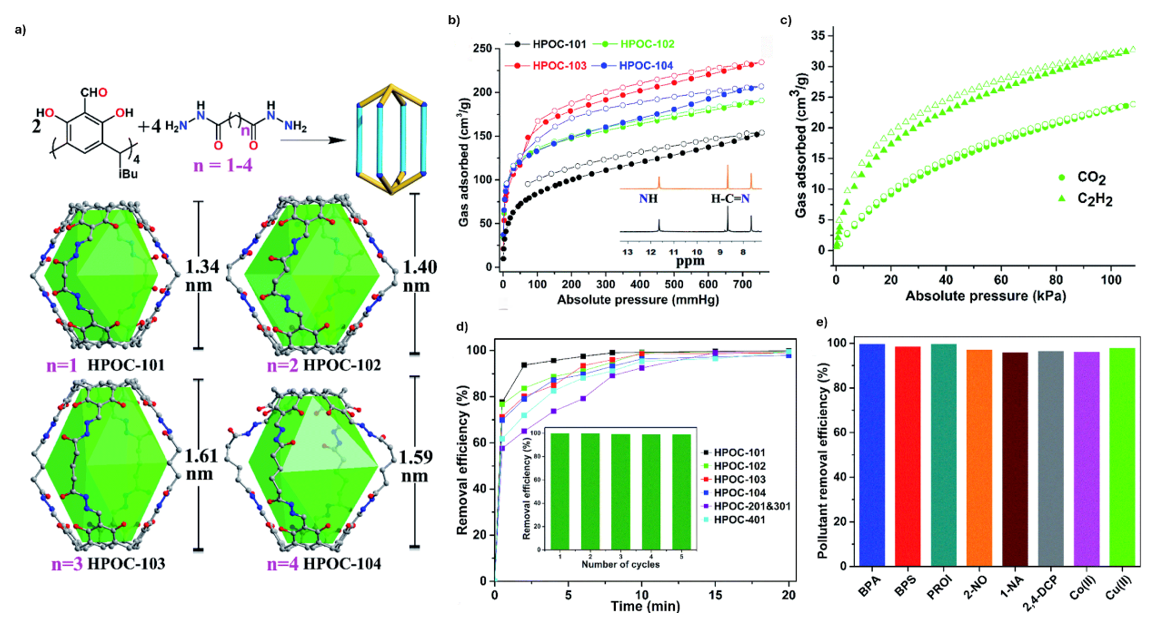

HPOC-101 to 104: water-stable POCs

The second example of porous organic cages is represented by the HPOC-101 to 104 series, which were obtained by a hydrazone condensation between tetraformylated calix[4]resorcinarene and a set of alkanedihydrazide linkers of increasing length (n=1-4) (Fig. 7a).15 It is a bowl-shaped macrocyclic molecule derived from resorcinol and aldehydes, and in this system the four aldehyde groups at its upper rim act as reactive sites for cage formation. The resulting architectures adopt lantern-like geometries in which two units are bridged by the dihydrazide linkers. By varying the linker length, the cages display progressively larger internal cavities, from 1.34 nm in HPOC-101 to 1.61 nm in HPOC-103. In the case of HPOC-104, the use of the longest linker introduces additional conformational flexibility, leading to a less regular, distorted lantern structure, though the cage cavity remains accessible for guest binding.

A key feature of these cages is their high stability in aqueous media, which is uncommon among POCs (Fig. 7b). This stability enables their use in a broad range of water-related applications. In addition to gas adsorption studies, where HPOC-102 shows efficient uptake of CO2 and C2H2 (Fig. 7c), these materials have been demonstrated as highly effective adsorbents for organic micropollutants, toxic metal ions, and even radionuclides. For example, HPOC-101 exhibits rapid and high-capacity iodine uptake together with strong recyclability, as well as efficiency for removing contaminants such as bisphenol A (BPA), bisphenol S (BPS), propranolol hydrochloride (PROI), 2-naphthol (2-NO), 1-naphthyl amine (1-NA), 2,4-dichlorophenol (2,4-DCP), Co(II), and Cu(II), (Figs. 7d & 7e). The combination of permanent porosity, water stability, and versatile host-guest chemistry establishes the HPOC family as a distinct class of POCs with significant promise for environmental remediation.15

Fig. 7. a) Schematic illustration of the assembly of [2+4] lanterns, along with their single crystal X-ray structures and inner cavity heights. The hydrogen atoms and iso-butyl groups are omitted for clarity; b) CO2 adsorption isotherms of hydrazone-linked POCs at 196 K and 760 mmHg. Inset is the water stability tests of HPOC-101, black lines stand for pristine samples, and red lines represent the samples after being soaked in water for a week; c) CO2 and C2H2 adsorption isotherms of HPOC-102 at 298 K; d) time-dependent adsorption of aqueous I3-, inset: the recyclability of HPOC-101 for I3− removal; e) percentage removal efficiency of different water pollutants (0.1 mM) by HPOC-101 (0.5 mg mL-1). Reproduced with permission from reference 15.

Gas capture by hydrogen-bonded organic frameworks (HOFs)

HOFs are another interesting class of fully organic porous materials. HOFs form extended networks through hydrogen bonds, creating stable yet flexible structures with permanent porosity. These frameworks can be designed to have specific pore sizes and chemical environments, allowing selective adsorption and storage of gases. The non-covalent hydrogen bonds also give HOFs a degree of adaptability, enabling structural changes or self-healing in response to external conditions. The ability to fine-tune the pore environment and the chemical functionality of HOFs opens exciting opportunities for selective gas adsorption, separation, and storage, complementing and expanding the capabilities already demonstrated by POCs.

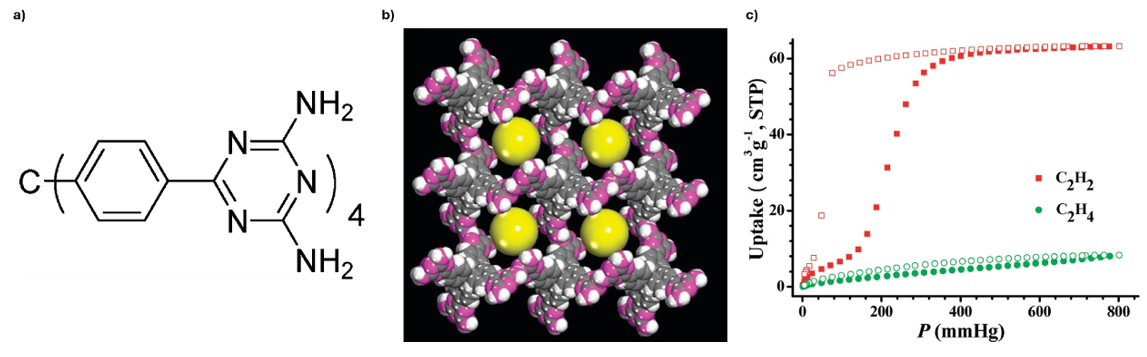

Selective C2H2/C2H4 separation in HOF-1

A representative example of the hydrogen-bonded organic framework family is HOF-1 (Fig. 8a). In this system, strong intermolecular hydrogen bonds direct the assembly of the organic linkers into an extended, crystalline porous network (Fig. 8b). The resulting framework exhibits permanent porosity and remarkable stability under ambient conditions, making it one of the earliest demonstrations that hydrogen bonding alone can generate robust porous solids.

Importantly, HOF-1 displays selective gas adsorption properties. As shown in the isotherm (Fig. 8c), it can distinguish between acetylene (C2H2) and ethylene (C2H4) at 273 K, with a significantly higher uptake of acetylene due to stronger host-guest interactions within its hydrogen-bonded pores.

This example highlights how relatively simple molecular building blocks, when organised through hydrogen bonding, can yield frameworks with useful selectivity for challenging gas separations.16

Fig. 8. a) Organic building block used to construct HOF-1; b) X-ray crystal structure of HOF-1 featuring one-dimensional channels along the c axis with a size of about 8.2 Å (yellow spheres); c) C2H2 and C2H4 sorption isotherms at 273 K. Reproduced with permission from reference 16.

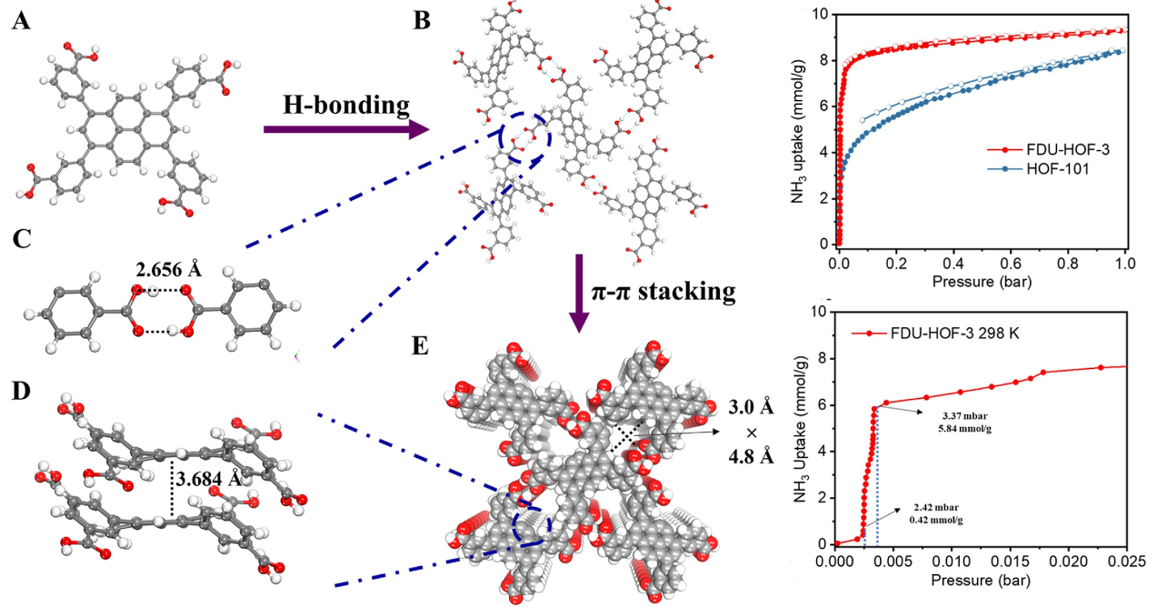

High-affinity ammonia adsorption in FDU-HOF-3

A more recent advance in HOF design is represented by FDU-HOF-3.17 This framework is assembled from a rigid, π-conjugated tetracarboxylic acid linker, stabilised through a combination of strong hydrogen bonding and π-π stacking interactions (Fig. 9). The resulting porous crystalline network features well-defined channels that enable efficient gas adsorption. Importantly, FDU-HOF-3 demonstrates excellent performance for ammonia (NH3) capture, with uptake capacities far exceeding those of HOF-101 (constructed from a pyrene-based carboxylic acid linker and widely regarded as a stable reference HOF).

As shown in the adsorption isotherms (Fig. 9), FDU-HOF-3 not only achieves superior uptake at moderate pressures but also captures appreciable amounts of NH3 even at very low concentrations. In addition, the framework maintains stability and recyclability over multiple adsorption-desorption cycles which highlights its potential for applications in noxious gas removal. The strong uptake arises from the combined effect of hydrogen bonding sites and the π-π stacked channels, which provide favorable interactions with ammonia molecules. This example illustrates how the integration of hydrogen bonding with π-π stacking can yield HOFs with exceptional sensitivity and capacity for toxic gas capture.17

Fig. 9. Crystal structures of the FDU-HOF-3 (A) H4PTTB (3,3′,3‴,3‴′-(pyrene-1,3,6,8-tetrayl)tetrabenzoic acid) ligand. (B) H-bonds in the single-crystal structure of FDU-HOF-3. (C) H-bonds of carboxylate dimers in FDU-HOF-3. (D) π-π stacking in FDU-HOF-3. € The 3D structure of FDU-HOF-3. NH3 adsorption-desorption isotherms of FDU-HOF-3 and HOF-101 at 298 K (top) and NH3 adsorption at low concentrations for FDU-HOF-3 at 298 K (bottom). Reproduced with permission from reference 17.

Lignin-derived porous materials

While hydrogen-bonded organic frameworks have shown impressive selectivity and tunable properties for gas separations, another class of materials is gaining attention for combining performance with sustainability: porous carbons derived from lignin. Lignin is a major byproduct of paper, pulp, and biorefinery industries, abundant and rich in carbon. By converting this waste into porous carbon materials, researchers aim to address two issues at once, by valorising a low value biomass and producing effective adsorbents for gases like carbon dioxide (and often ammonia, sulfur dioxide, etc.). These lignin-derived porous materials often exhibit very high surface areas, a range of pore sizes (from micropores that trap small gas molecules to mesopores that help with transport), and chemical functionalities that enhance adsorption. In the following examples, we highlight recent high-impact work showing how lignin-derived porous carbons are being designed and tested for CO2 capture and related gas separation.

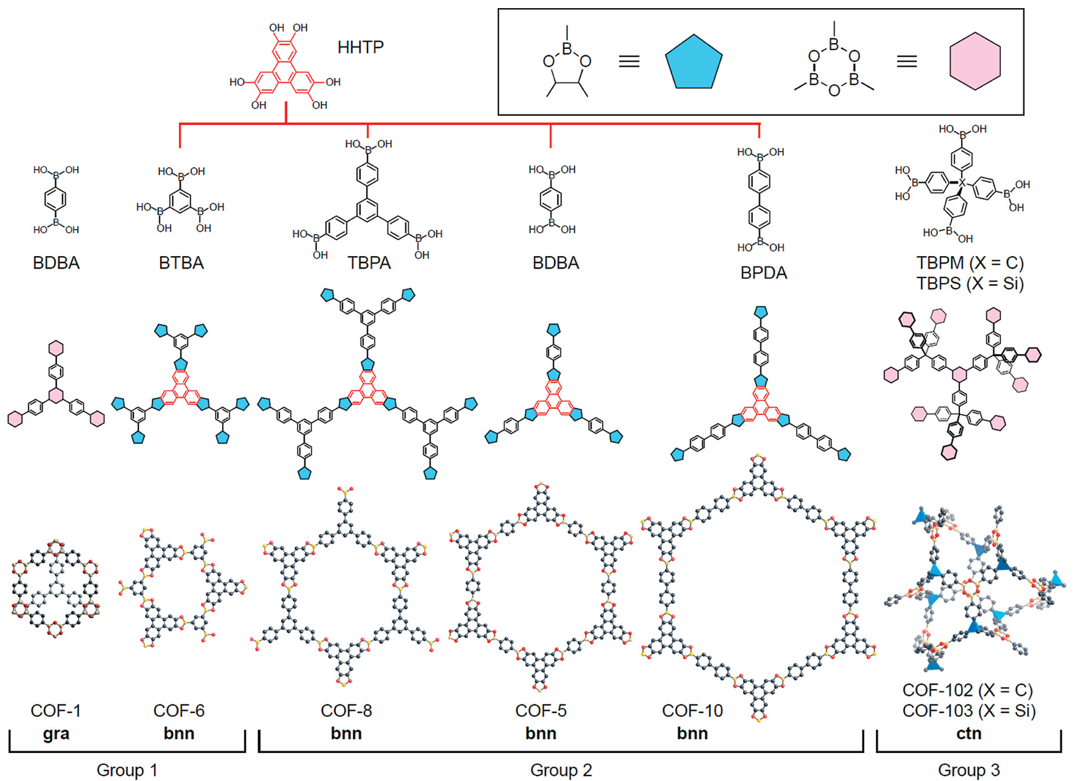

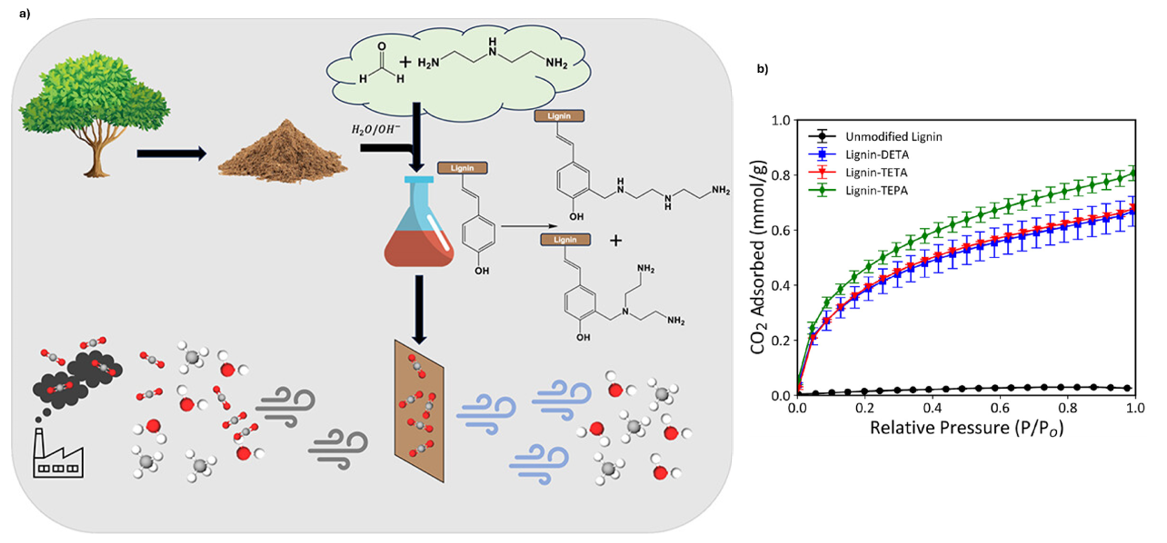

Amine-functionalised lignin for CO2 capture

In this approach, lignin was chemically modified with different polyamines to improve its affinity towards CO2. Fig. 10a illustrates how lignin was functionalised with diethylenetriamine (DETA), triethylenetetramine (TETA), and tetraethylenepentamine (TEPA). These amines introduce multiple nitrogen donor sites, which can reversibly interact with CO2 molecules through acid-base and carbamate formation mechanisms.

The adsorption isotherm (Fig. 10b) clearly demonstrates the effect of amine modification. While unmodified lignin shows negligible CO2 uptake, the functionalised samples exhibit markedly higher adsorption capacities, with performance increasing in the order DETA < TETA < TEPA. This trend reflects the growing number of amine groups available for CO2 binding as the chain length of the polyamine increases. Importantly, the study shows that simple chemical modification can transform lignin from a low-value biomass into an effective and scalable sorbent for direct air capture.18

Fig. 10. a) Schematic representation of lignin functionalisation with polyamines to create nitrogen-rich sorbents for CO2 capture; b) CO2 adsorption isotherm of unmodified lignin and aminated lignin sorbents. Reproduced with permission from reference 18.

Polymers of intrinsic microporosity (PIMs)

PIMs are rigid, contorted polymers that cannot pack efficiently, leaving permanent tiny pores for gas transport. Unlike POPs, which are insoluble, PIMs are soluble in common organic solvents and can be easily processed into thin membranes. This makes them especially useful for CO2 separation, where they combine very high permeability with good selectivity, and can be further improved through functionalisation or crosslinking.

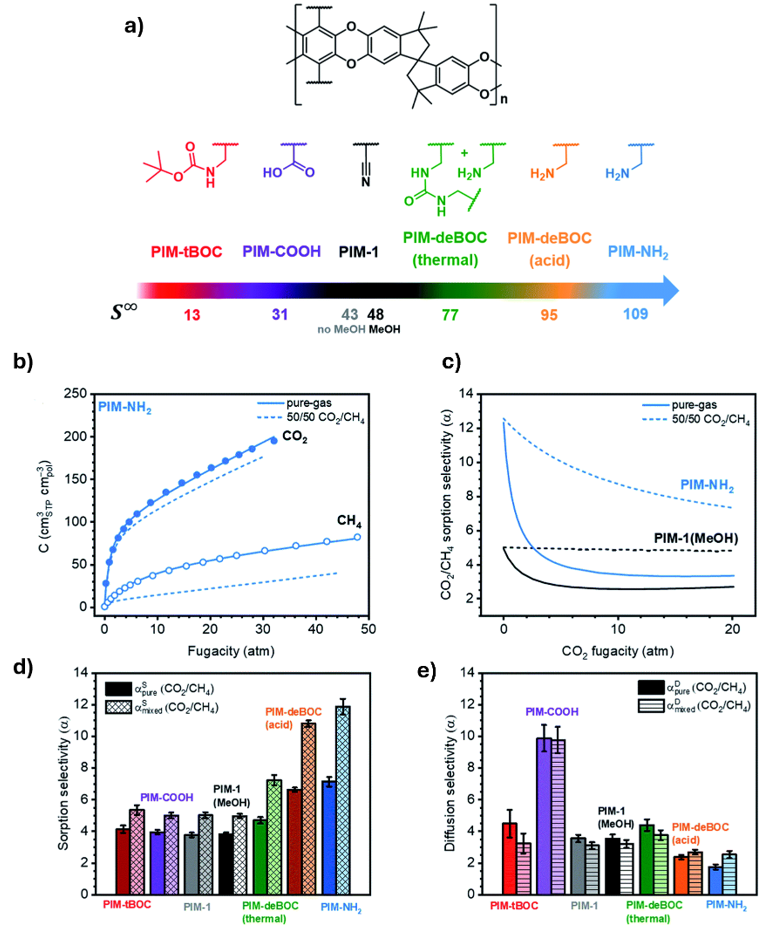

Functionalised PIM-1 for enhanced gas separation

The gas separation behavior of PIM-1 can be significantly tuned by chemical modifications. The parent PIM-1 structure was functionalised with different functional groups such as carboxylic acid (-COOH), amine (-NH2), and Boc-protected amines, each altering the polymer’s interaction with gases. As shown in Fig. 11, CO2 sorption increases markedly for the amine-modified variants, while the CO2/CH4 selectivity is also enhanced compared to unmodified PIM-1. Among them, PIM-NH2 exhibits the highest uptake and selectivity, demonstrating how introducing amine functional group strengthens CO2 affinity. These results underline the importance of structural tuning in PIMs, where relatively simple chemical modifications can yield membranes with superior CO2 separation performance.8

Fig. 11. a) Chemical structures of PIM-1 and its functionalized derivatives along with their corresponding sorption coefficients at infinite dilution; b) pure-gas CO2 and CH4 sorption isotherms for PIM-NH2. Open (CH4) and filled (CO2) symbols denote experimentally collected data; c) pure-gas CO2 and CH4 sorption selectivities (solid lines) and predicted 50/50 CO2/CH4 sorption selectivities (dashed lines) for PIM-NH2; d) pure and predicted mixed-gas sorption selectivities at a CO2 partial fugacity of 1 atm; e) pure and mixed-gas diffusion selectivities calculated using the sorption–diffusion model at a CO2 partial fugacity of 1 atm. Reproduced with permission from reference 8.

Conclusions

Porous organic materials provide a broad and flexible platform for tackling the challenge of climate change through selective gas capture and separation. Framework-based systems such as COFs and HOFs demonstrate how extended crystalline networks can deliver permanent porosity with high structural tunability, whereas discrete molecular cages (POCs) offer well-defined, shape-persistent cavities that can be engineered for selective gas uptake. Polymeric systems, including POPs and PIMs, highlight the versatility of organic polymers, extending insoluble crosslinked sorbents to solution-processable membranes suited for large scale CO2 separations. Complementing these synthetic approaches, lignin and other biomass-derived porous carbons introduce sustainable and cost-effective options that value natural resources.

Together, these classes emphasise that there is no single “universal molecular sponge”, but a spectrum of complementary solutions. Future progress will depend on integrating their individual strengths, such as precise design in frameworks, molecular selectivity in cages, scalability in polymers, and sustainability in biobased carbons, and addressing challenges such as long-term stability, selectivity, and industrial-scale production. Such efforts will be essential for translating porous organic materials from laboratory studies into practical tools for carbon management and climate mitigation.

References

- Eddaoudi, M.; Kim, J.; Rosi, N.; Vodak, D.; Wachter, J.; O'Keeffe, M.; Yaghi, O. M. Science 2002, 295, 469-472.

- Song, K. S.; Fritz, P. W.; Coskun, A. Chem Soc Rev 2022, 51, 9831-9852.

- Feng, X.; Ding, X.; Jiang, D. Chem Soc Rev 2012, 41, 6010-6022.

- Yang, X.; Ullah, Z.; Stoddart, J. F.; Yavuz, C. T. Chem Rev 2023, 123, 4602-4634.

- Deng, W. H.; Wang, X.; Xiao, K.; Li, Y. B.; Liu, C. L.; Yao, Z. Z.; Wang, L. H.; Cheng, Z. B.; Lv, Y. C.; Xiang, S. C.; et al. Chem Eng J 2024, 497, 154457.

- Barker-Rothschild, D.; Chen, J.; Wan, Z.; Renneckar, S.; Burgert, I.; Ding, Y.; Lu, Y.; Rojas, O. J. Chem Soc Rev 2025, 54, 623-652.

- Astorino, C.; De Nardo, E.; Lettieri, S.; Ferraro, G.; Pirri, C. F.; Bocchini, S. Membranes (Basel) 2023, 13, 903.

- Mizrahi Rodriguez, K.; Benedetti, F. M.; Roy, N.; Wu, A. X.; Smith, Z. P. J Mater Chem A 2021, 9, 23631-23642.

- Wu, Z. Q.; Li, Z.; Hu, L.; Afewerki, S.; Stromme, M.; Zhang, Q. F.; Xu, C. Green Chem. 2024, 26, 10960-10968.

- Yan, J.; Zhang, B.; Guo, S. W.; Wang, Z. G. Acs Appl Nano Mater 2021, 4, 10565-10574.

- Furukawa, H.; Yaghi, O. M. J Am Chem Soc 2009, 131, 8875-8883.

- Lyu, H.; Li, H.; Hanikel, N.; Wang, K.; Yaghi, O. M. J Am Chem Soc 2022, 144, 12989-12995.

- Zhang, Z.; Kang, C.; Peh, S. B.; Shi, D.; Yang, F.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, D. J Am Chem Soc 2022, 144, 14992-14996.

- Zhang, G.; Presly, O.; White, F.; Oppel, I. M.; Mastalerz, M. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 1516-1520.

- Yang, M.; Qiu, F.; ES, M. E.-S.; Wang, W.; Du, S.; Su, K.; Yuan, D. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 13307-13315.

- He, Y.; Xiang, S.; Chen, B. J Am Chem Soc 2011, 133, 14570-14573.

- Song, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Gao, X.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, B.; Li, P. J Am Chem Soc 2024, 146, 627-634.

- Carrier, J.; Lai, C. Y.; Radu, D. ACS Environ Au 2024, 4, 196-203.

Acknowledgements

The author sincerely thanks Professor Nigel Lucas & Dr Yanfang Wu for their valuable feedback and suggestions.