First published in Chemistry in New Zealand in April 2017 and authored by the late Professor Brian Halton.

Thomas Hill Easterfield was born on March 4, 1866 in Doncaster, Yorkshire, England, the son of Edward and Susan (neé Hill) Easterfield. His father was a banker who rose to become secretary and then manager of the local branch of the Yorkshire Savings Bank. Thomas Easterfield entered Doncaster Grammar School and won prizes in Classics, divinity, French, German and science during his time there.1,2 His younger years had him contemplating a career in the textile industry by study in the department at Yorkshire College Leeds (the forerunner of Leeds University). In May of 1881 he won one of the Akroyd Scholarships3 (in geology4) valued at £20 annually for two years to attend the college. He subsequently became a Brown Scholar and published two papers, one on photography,5 the other on a glacial deposit6 from his time there. Although not previously noted,1,2,4,7-10 his time at Yorkshire College led to the award of a BA degree. This is given as his first qualification in the October 29, 1931 invited application to join the New Zealand Institute of Chemistry as a founding member (see below).11 Initially he was an Associate, then ten years later in 1941 he became a Fellow. From Leeds, Thomas proceeded to Cambridge’s second oldest college, Clare, as a senior foundation scholar studying geology, physics and chemistry, and being awarded a first-class degree with honours in chemistry and geology in the natural science tripos in 1886. As an aside, shortly after Easterfield left Leeds, the famous ‘penny bazaar’ started in 1884 as a stall in the Leeds Kirkgate Market, and went on to become Marks and Spencer, one of the UK’s largest chain stores. Apart from his academic acumen Easterfield was a notable middle-distance runner, representing the university in the mile and three-mile events, the former at the Oxford-Cambridge meetings over 1886-1888. He became a Cambridge blue.

%20Application%20NZIC-1%20ED.jpg)

Following his time at Cambridge, Easterfield gained postgraduate experience at the Zurich Polytechnic College and the University of Zurich in Switzerland, and then at Würzburg University on the Main river in Germany. There he worked under the noted organic chemist Emil Fischer who had him study two topics, one relating to the structure of sugars and the other to the three-dimensional structure of carbon compounds,1 with his PhD work on the chemistry of citrazinic acid (1) that was also started there. His doctoral degree was awarded in 1894 based on a 35-page thesis entitled: Zur Kenntnis der Citrazinsäure (knowledge of citrazinic acid).

There is some confusion as to precisely when Easterfield went to Würzburg but he returned to Cambridge in 1888 as a lecturer under the University Extension Movement, and worked in the University Organic Chemistry Laboratory according to Marsden,8 or as Davis1 gives it a demonstrator in the chemical laboratory, became university extension lecturer and was, for a while, part-time science master at Perse Grammar School in Cambridge. In contrast, MacFarlane2 tells us that Easterfield appears to have returned to England several times during his PhD studies and gained a variety of practical experiences, especially over the 1891-1894 period and prior to the award of his PhD degree. Irrespective of the precise detail here, Easterfield’s publications on the topic of his PhD are jointly with W.J. Sell,12 a demonstrator at Cambridge who had published from that position On the Volumetric Determination of Chromium in the Transaction of the Chemical Society in 1879. Moreover, Sell published on derivatives of citric and aconitic acids with Easterfield in 1892 and continued with the citrazinic acid study until after Easterfield left Cambridge, publishing the results with F.W. Dootson in 1897 and with H. Jackson in 1899. It is the view of this author that much if not most of the Easterfield PhD experimental work could have been performed in Cambridge with Sell as the assistant supervisor. Easterfield’s ability to teach, lecture, and research grew over the 1887-1894 period as judged from his twelve publications from that period.13 As important is the fact that during his time in Germany, Thomas met and courted Bavarian Anna Maria Kunigunda Büchel and married her in Würzburg on September 1, 1894.

From Würzburg, Easterfield returned to Cambridge in 1894 to a lectureship in pharmaceutical science and in the chemistry of sanitary science.7 He filled these positions with success and continued his research studies publishing a further four papers on aspects of charcoal, Indian hemp resin (Cannabis sativa), and cannabinol. When the Victoria College Wellington Board chose to appoint its inaugural professors, four chairs were advertised, one being in chemistry and physics. Easterfield applied for this, was interviewed in England, and accepted the offer of appointment as announced in the New Zealand Herald, on January 13, 1899. His appointment came with funds to purchase and ship needed scientific equipment, £100 for the physics and £50 for chemistry were initially allocated, spent and the supplies dispatched, only to be damaged in transit. Subsequently, the situation was made passable with the gift of £25 from George W. Wilton, the founder of what became one of New Zealand’s major importers of scientific equipment through the 20th century.

Easterfield, his wife, and by then two daughters, joined John Rankine Brown (Classics) and his family on the steamship Kaikoura in Plymouth for their travel to New Zealand on the evening of February 11th, 1899, in the foulest of weather. Hugh MacKenzie (English Language and Literature) and his family had boarded in London. The Brown and Easterfield families were taken out to the ship by tender, and were in a bedraggled and collapsed condition when they reached it in Plymouth Sound. When the Kaikoura put out to sea things were even worse, for she headed into a first class gale which lasted three days and destroyed a large part of the captain's bridge. However, the sea was calm and pleasant by the time they reached Tenerife, and on rounding the Cape the three professors had learned something of one another's idiosyncrasies.14 The fourth appointee, the unmarried Richard Maclaurin, came independently via the US, arriving in Auckland and transferring to Wellington.15

The Kaikoura sailed into Wellington harbour on Saturday, April 1, 1899, one of Wellington’s glorious autumnal days. If, on that 1st of April when the Council met them (the professors), they had felt a little foolish they might be forgiven. Somehow, before they left England, they had been given to understand that their college was not only adequately endowed, but actually physically in existence - that their task as founders was, as it were, to walk in and begin lecturing.15 The reality was very different. There was no college edifice and little finance. On being met by the college councillors, Easterfield was told by one that he had gained his appointment by just one vote – and that because there was no Scotsman available! The professors were given a little time to accustom themselves to their new surroundings before a formal welcome in the offices of the Education Board on Wednesday April 12. However, the first students registered just one week after their arrival and were met by the professors. Term 1 started on April 18 with 30 students in chemistry and 11 in physics. The first two of the inaugural lectures were presented that same evening.16,17 In his address, Research as a Prime Factor in Scientific Education,18 Easterfield espoused his views on education and to a colonial audience 118 years ago he must have seemed a revolutionary. He was the inaugural appointee of the four who came German-trained with a definite purpose. He was plain in saying that early specialisation by students with research work and original investigation should come before a degree was awarded and that a good laboratory was an absolute necessity for staff and student research in science. That some of the research could benefit the country also had to be recognised. Research was in marked contrast to the reality of Wellington College. There was no building and no facilities for science. Consideration had been given to using a boarding house on Tinakori Road (now the Prime Minister’s formal residence) for the college but that was discarded after Easterfield announced that the ground floor could be suitable for science but not the upstairs bedrooms. After the term started, three upper rooms in the Technical School Building on Victoria Street were made available.17 It was there that Easterfield fashioned a laboratory himself out of boards and trestles.

The balance that Easterfield had been given by his Cambridge colleagues, and a prize possession, was placed on a packing case in one corner. It was here that science was taught and where Thomas Easterfield began his New Zealand researches carrying out his own experiments and directing those of his students. There was no assistant and no lab attendant (a technician in the modern idiom), and the students had to bring up the water and empty the slop buckets themselves. On one occasion this was missed and the corrosive liquid ate through the bucket, permeated the ceiling, and made a significant mess in the Technical School Director’s office directly below.16,19 The adjacent room was the physics laboratory and lecture room, from which the students were required to remove their chairs and collapsible tables when they left - much to the annoyance of those in the room below. Yet, such primitive surroundings did not deter the research efforts. Early students gained notable college honours and the enthusiasm of the foundation professor was undeterred in establishing his discipline.

During that first year of 1899, Easterfield and Victoria College secured £3000 for equipping the laboratories. When the students arrived back for the 1900 teaching year the upstairs rooms of the Technical College had been transformed and a chemistry laboratory created, this to the extent that the arts students from below asked to come and draw it. One of these budding artists, Sybil Johnson, painted what was to Easterfield the most beautiful representation of his creation.16 This painting became part of his collection, subsequently to be donated to the University College by his widow. His own researches were dominated by New Zealand natural products involving native plants, to which he had referred in his inaugural lecture. Easterfield used the laboratory fund wisely, and when the university opened its building in Kelburn in 1906 some of the facilities had been paid for from the residue of the fund and the kauri laboratory benches transferred from their city location. When tenders were called for what became the Hunter Building, Easterfield was not backward in coming forward. In his view, the instructions given to the architects were rather vague and three of the firms approached him for his opinion on the College Building. This he offered, not just to those three but to all the contenders, and the edifice that stands carries many of his ideas. During his first decade at Victoria he held the chairs of chemistry and physics and was relieved of the latter only in 1909 with the appointment of Prof. T.H. Laby.

In his second year, he not only published his own research results with B.C. Aston, the government chemist in the Department of Agriculture, but also read the paper of one of his first students, P.W. Robertson, to the New Zealand Institute (Wellington), the forerunner of the Royal Society of New Zealand. Easterfield was quick to introduce himself to the few chemists in Wellington, notably William Skey, who was the Colonial Analyst in Wellington, and Aston. With Aston, he set to work on the Tutu plant (Coriaria) and isolated the poisonous principal which they named tutin (2). Their work was published on the three species of coriaria found in New Zealand, namely C. ruscifolia, C. thymifolia, and C. angustissinza, firstly in this country and then in the UK in 1900 and 1901, respectively.20 Their collaboration continued with studies of karaka (Corynocarpus laevigatus) and rimu (Dacrydium cupressinum) resin, which is now known to contain podocarpic acid (3).

Easterfield continued his work teaching, carrying out research, and directing his students, most of whom went on to notable careers in New Zealand science. He was also consultant to industry but the difficulties in funding research and the limited recognition his efforts drew began to weigh more heavily on him and his interests moved more towards agricultural chemistry from about 1908. Nonetheless, his research was recognised in 1913 with the award of the second of the New Zealand Institute's Hector Memorial Medal and Prize. Then, during the Great War with shortage of synthetic medicines he processed the opium seized by the police under New Zealand’s anti-drug laws in his Victoria laboratory to provide morphine.21 His consultancies are nicely illustrated by some of his last experiments as College Professor that were performed at the Miranui flax mill near Levin. These were to determine if industrial alcohol (ethanol) could be produced by fermenting the juices of the flax leaf. This factory was the largest and most well equipped mill of the era and his test runs produced 198.4 gallons of 95% ethanol daily. This was not used but allowed to flow down the Miranui drains! The output equates to 50,000 gallons per annum and would have been worth £3750 per year at 1s 6d per gallon in 1919.16

Following the death of Thomas Cawthron in 1915, the will that the gentleman made in London some thirteen years earlier was granted probate by the Supreme Court in Wellington on November 12, 1915. The bulk of the £250,000 estate was set for the purchase of the erection and maintenance of an industrial and technical school institute and museum in Nelson, New Zealand, to be called the Cawthron Institute.22 The suggestion that most of this wealthy bachelor’s estate could be put to such usage was made by Cawthron’s friend Joseph H. Cock when asked how best his wealth could be divided.22,23 As the executors had little knowledge or understanding of science they established an advisory commission to which Easterfield was appointed along with Professors Benham (Biology, Otago) and Worley (Chemistry, Auckland), the noted biologist Leonard Cockayne, and Sir James Wilson, President of the Board of Agriculture; Easterfield was appointed secretary. As with everything he did, Thomas Easterfield was thorough, conscientious and efficient. Within three months of arriving in Nelson the advisory commission’s report had been sent to the trustees and gone for legal approval. As secretary, Easterfield was asked to report on the form and functions of the yet to be established institution and in 1917 he presented the aims and ideals of the trustees at a public lecture in Nelson. It became the first annual Cawthron Memorial Lecture. When it came to the appointment of the first director, the trust board had two candidates in mind – Easterfield and his former student Theodore Rigg. The older Easterfield had all the attributes that the trustees considered essential for its inaugural director and he was appointed Founding Director in October 1919. By then he had given all that he could to establishing chemistry at Victoria University College as it then was, and he accepted the offer. He then had to live up to his comments in the Cawthron Lecture – that the Institute would have a bright future! During his 21 years at Victoria, Easterfield published no less than 26 papers,2 several of them in this country then with the Chemical Society (UK); 23 of them are recorded in SciFinder©. Easterfield’s research record at Victoria (University) College was solid and particularly significant as research was not high on the agenda of the New Zealand University Colleges during his tenure. He was appointed Victoria’s first emeritus professor.

As founding director of The Cawthron Institute in Nelson, Easterfield found himself in a position akin to that on his arrival in Wellington. Although the Cawthron Trustees had purchased land and property on a 10.4 acre site in Annesbrook in 1917, and some five kilometres from the city, conversion to the facilities of a scientific Institute did not happen. Half the property was kept as an orchard almost until 1959, but as in Wellington in 1899, Thomas Easterfield had to make do with temporary accommodation. This was until Fellworth House, the John Sharp property on Milton Street, was bought later in 1920.22 The house stood in three acres of ground and consisted of some fifteen rooms that were modified for science usage. The trustees had recognised early on that the strengths of the Cawthron would be in agriculture and horticulture, and it was in this area that Easterfield directed his attention. This contrasts with his 1917 lecture in which he was clear that research should not be restricted to applied areas but include ‘pure science’.

During his first year, Easterfield appointed Theodore Rigg as his assistant and agricultural chemist and then W.C. Davies (museum curator and photographer), Drs. R.J. Tillyard (entomologist) and Kathleen Curtis (mycologist who became the first woman elected to RSNZ Fellowship in 1936), H. Harrison (librarian), and two technicians A Philpott and E.J. Champtaloup. And then he gave each of the scientists the ability to appoint their own technicians. This engendered a good staff with excellent working relationships and loyalty to the Institute.22 These appointments doubled the country’s agricultural research capacity and were followed in 1921 by a fifth position in orchard chemistry part funded by the fruit growers association. They gave Nelson an intellectual force.23

From taking up his position, the Cawthron Institute was the sole organisation devoted to agricultural and horticultural problems not simply in New Zealand but in the entire southern hemisphere. Requests for assistance had started to arrive shortly after Cawthron’s will was made public, but Easterfield elected to address those of the Nelson region first. The Cawthron’s main departments of scientific research, horticulture and agriculture were established in 1920 with a sound chemical base, and these were maintained with little change until a Biochemical Department was added at the end of 1941 to handle plant and animal nutritional problems more effectively. Easterfield’s profound belief in research was applied as vigorously with his colleagues at The Cawthron as it had been in Wellington and a voluminous quantity of research was published during its first decade leading to the international reputation that the institute gained.

From the turn of the century, second-class back blocks of land had been brought into production in the area, not least in the immediate post-war years. One of the early needs came from the pipfruit growers to improve their soils and to rid their crops of woolly aphis, bitter pit, black spot and codling moth.22,23 Tillyard went to the UK to learn about woolly aphis and persuaded Easterfield to acquire one of the best entomological libraries in England that was then available. Kathleen Curtis attacked the black spot problem, while Rigg attended to the poor Moutere soil. Their combined studies were of immense value to the industry and were seen in improved yields and quality of the fruits. The woolly aphis problem was essentially solved by 1930 when spraying of apple trees was no longer needed following introduction of the Aphelinus mali, the elucidation of the life history of the black spot fungus of apples led to its eradication, and the fertiliser requirements of the Moutere Hills (and other soils) were solved or, at worst, improved in other areas. Furthermore, the Cawthron identification of the major causes of apple storage defects were of great value not only to the apple industry of Nelson but to fruit culture throughout New Zealand. The impact of the Cawthron work had the whole of the fruit growing business back in boom by 1926 when the crop output exceeded the shipping capacity. Apple exports soared from 6000 to 227,000 cases and by 1930 the acreage was so high and the demand for seasonal pickers so great that there was no accommodation left available for them. The tobacco industry also prospered with the number of growers in Waimea County rising from 150 to 700 between 1926 and 1933.

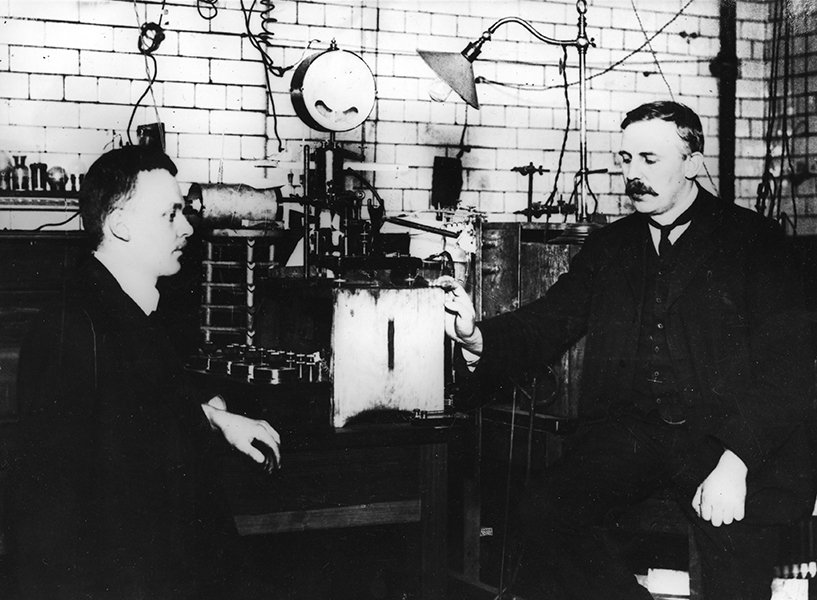

As director of the Cawthron Institute, Thomas Easterfield played an important role in its establishment and in the development of research programmes. The early phenomenal success of the Institute was due in large measure to his enthusiasm, broad vision, and sound judgment in selecting the pioneer staff. But, as for all research establishments, funding was an on-going concern. The requirement of stamp duty on the Cawthron bequest reduced the interest returns and the continuing existence of the Institute depended on grants, donations and bequests. The lack of funding expressed itself as early as 1923 when Thomas Easterfield paid the salary of one his staff from his own pocket because there were inadequate monies available. The lack of funding was felt most strongly by Easterfield from his inability to undertake pure research in his time. Monies were subsequently boosted following the 1925 visit to Nelson of Sir Ernest Rutherford and then the 1926 visit of Sir Francis Heath that rapidly led to the establishment of the New Zealand DSIR. Easterfield’s researches at the Cawthron led to ten publications, three on mineral oils of New Zealand and two on the occurrence of xanthin (4) [a close relative of caffeine (5)] in sheep, all of a technical nature.

What Easterfield did with aplomb was to gain the trust of the industries and to provide them with relevant pamphlets and other appropriate educational aids, and become a friend of the local farmers, growers and industrialists, as well as a noted figure in the Nelson community. To his staff he was a man to be emulated. Elsa Kidson, a staff member at the Cawthron and first female demonstrator in a New Zealand University, recounted in an unpublished address given to the P.W. Robertson Society (an organization for Victoria’s chemistry students and graduates established in 1970) on April 9, 1974: I found him able to instil confidence and make me feel more capable, I am sure, than my abilities justified ….. but I can say that I never heard a word of criticism against him. He was always courteous and I never saw him get angry.2, 24 He was easily approachable, had a great sense of humour, and was a great reader in his spare time.

In the first Cawthron Lecture, Easterfield had said:

I foretell a brilliant future for the Institute. The problems solved in it will lead to results of the greatest value to this city, the Dominion and to the human race. And the Institute itself is destined to become a centre of light, learning and culture honoured throughout the civilised world and a lasting tribute to Thomas Cawthron.

The results of his labours as Director of the Institute show that not only was Easterfield a dedicated founding chemist in this country, but that his ability to tell the future also was accurate.

In 1933 on the eve of his retirement, he delivered the annual Cawthron lecture that was entitled The Thomas Cawthron Centenary Lecture in which he summarised the successes of the Institute from its inception to that date.25 Because of the role the Cawthron Institute played in solving the district fruit and dairy problems, the Nelson area was not impacted upon to the same extent as the rest of this country during the Great Depression of the 1930s. Moreover, the establishment of the McKees Fruitgrowers Chemical Company from 1931 in an abandoned coolstore in Mapua next to the wharf made the needed chemicals easily available in that era when chemical aids were regarded more favourably than now.23 The successes of the Cawthron Institute over the early years are also appropriately described by Miller in his 1963 book Thomas Cawthron and the Cawthron Institute26 and the reader may wish to refer to it.

Thomas and Anna Easterfield had five children, two daughters before they arrived from England and then two more daughters (Muriel Helen; February 26, 1900 and Theodora Clemens; June 12, 1902) and a son (Thomas Edward; 1912) all of whom distinguished themselves. The two New Zealand born daughters became medics whilst Edward gained an MSc from Canterbury University College in 1934 (following private school education in Wellington and Nelson) and subsequently an overseas PhD and a career becoming a Principal Scientific Officer in the DSIR in London. Thomas Hill Easterfield died in Nelson on March 1, 1949, survived by his wife and children. He made an outstanding contribution to science in New Zealand. Remembered for his high spirits and cheerfulness, he set high standards in the training of students and in the conduct of chemical research. He established two notable institutions in Victoria's chemistry department and the Cawthron Institute. It was his vision, judgement and enthusiasm for research that set chemistry in Wellington on track and brought the Cawthron to the international position it was to hold at his retirement and maintains today.

Thomas Easterfield was appointed to the New Zealand Order of Merit in 1925, was awarded a King George V Silver Jubilee Medal in 1935, and knighted (KBE) in 1938. He was a Fellow of the New Zealand Institute that became The Royal Society of New Zealand and its 1921-1922 President, a Fellow of the NZIC, and a member of many other chemical societies.

Acknowledgement

I am grateful to Richard Rendle for suggesting the topic and providing Easterfield’s NZIC application form, and to Andrea Mead of the Cawthron Institute for assistance and the provision of much useful information especially through reference 22.

References and Notes

- Davis, B.R. Easterfield, Thomas Hill, from the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, see: http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/3e1/easterfield-thomas-hill (accessed 23/09/2016).

- MacFarlane, D.R. T.H. Easterfield: Science in Colonial New Zealand, BSc Hon. Rpt. 1978, 18 leaves VUW Library Q143 E13 M143.

- Data reported in the Leeds Mercury, 14 May 1881.

- Mackay, D. An Appetite for Wonder - Cawthron Institute 1921-2011, Cawthron Institute, 2011, Ch. 2, 35-56.

- Easterfield, T.H. The Interaction of Solutions of Alum and Sodium Thiosulphate, Leeds Photographic Society, 1883.

- Easterfield, T.H. A Glacial Deposit near Doncaster, Yorkshire Geological Society, 1883, 8, 212-213.

- Easterfield, Sir Thomas Hill, KBE, from An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand, A.H. McLintock (ed), 1966. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, see: http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/1966/easterfield-sir-thomas-hill-kbe (accessed 26/09/2016).

- E. Marsden, E. Obituary notices: Thomas Hill Easterfield, 1866-1949, J. Chem. Soc. 1952, 1557, see: http://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/1952/JR/jr9520001557#!divAbstract (accessed 28/09/2016).

- Miller, D. Obituary: Sir Thomas Hill Easterfield, KBE, Nature 1949, 163, 669-669, see: www.nature.com/nature/journal/v163/n4148/abs/163669a0.html (accessed 27/09/2016).

- Askew, H. O. Obituary: Thomas Hill Easterfield (1866–1949), Trans. Proc. Royal Soc. NZ, 1950, 78, 381–383 (accessed 28/09/2016).

- I thank Richard Rendle for providing the application from the Institute archive.

- Easterfield, T.H.; Sell, W.J. Studies on citrazinic acid, Pt.1, Trans. Chem. Soc. 1893, 63, 1035-1051, Pt. 2, Trans. Chem. Soc. 1894, 65, 28-31 ; Pt.3, 1894, 65, 828-834.

- MacFarlane, D.R. See Appendix entries in ref. 2 above.

- Easterfield, T.H. A Foundation Professor Writes of the Early Years, Spike, The VUC Review Golden Jubilee Number, 1949, May, 19-22.

- Beaglehole, J.C. Victoria University College – an Essay towards a History, NZ University Press, Wellington 1949.

- Halton, B. Chemistry at Victoria –The Wellington University, School of Chemical & Physical Sciences, Victoria University of Wellington, 2nd edn. 2014, pp. ix, 173 available for complimentary download at: http://www.victoria.ac.nz/scps/about/attachments/ChemHist_second-edition_lowres.pdf (4 MB file).

- Barrowman, R. Victoria University of Wellington, 1899-1999 a history, Victoria University Press, 1999, pp. 432.

- Easterfield, T.H. In: Inaugural Addresses of the Victoria University College, Turnbull, Hickson & Palmer, Wellington 1899, 36-43, Victoria University of Wellington library LG741 VU A2, pp 54.

- Easterfield, T.H. The Development of Science at Victoria College, Spike, The VUC Review, 1924, Easter, 44-47.

- Easterfield, T.H.; Aston, B.C. The Tutu Plant Part 1, Trans. NZ Inst. 1900, 33, 345-355; J. Chem. Soc. Trans. 1900, 16, 211-212; J. Chem. Soc. Trans 1901, 79, 120-126.

- Soper, F.G. Chemistry in New Zealand, Chem.in NZ, 1975, 39, 97–101.

- MacKay, D. An Appetite for Wonder: Cawthron Institute 1921-2011, Midas Printing (China) for the Cawthron Institute, 2011, pp. 231.

- McAloon, J. Nelson: a regional history Cape Catley in association with Nelson City Council, Whatamango Bay, Queen Charlotte Sound, New Zealand 1997 –see p. 157-163.

- Burns, G.R.; Duncan, J.F.; Shorland, F.B. T.H. Easterfield on the 75th anniversary of the Founding of the Chemistry, Chemistry Department Report No. 4, 9 April 1974, VUW library QD1 V645 R 4.

- Easterfield, T.H. The Achievements of the Cawthron Institute, The Cawthron Institute, Evening Mail Office, Nelson, 1934, Victoria University of Wellington library AS750 NEL C.

- Miller, D. Thomas Cawthron and the Cawthron Institute, Cawthron Institute, 1963; pages 95-136 give an summary to the important work of the Institute over the earlier years.