Abstract

Historical indigenous applications of plants for medicinal uses are well known across the globe and in Aotearoa, with many medicinal applications arising from naphthoquinones (NQ), anthraquinones (AQ) and their quinol (QL-GLY) or quinone glycosides (Q-GLY). This review highlights the biosynthetic pathways of these glycosides followed by their complexity and functionality, along with an analysis of the general methods to identify and isolate these compounds. Their medicinal properties, synthetic functionalisation, applications and potential are covered, including how these compounds may be linked to traditional plant uses, and how this provides a deeper understanding of unique cultures. Finally, their occurrence in Aotearoa, association with Mātauranga Māori (traditional Māori knowledge) – particularly in Dianella (flax lilies), Phormium (harakeke), Coprosma (karamu) and Bulbinella - and previous/current work in this space, including what gaps future work could focus on, are also explored.

Introduction

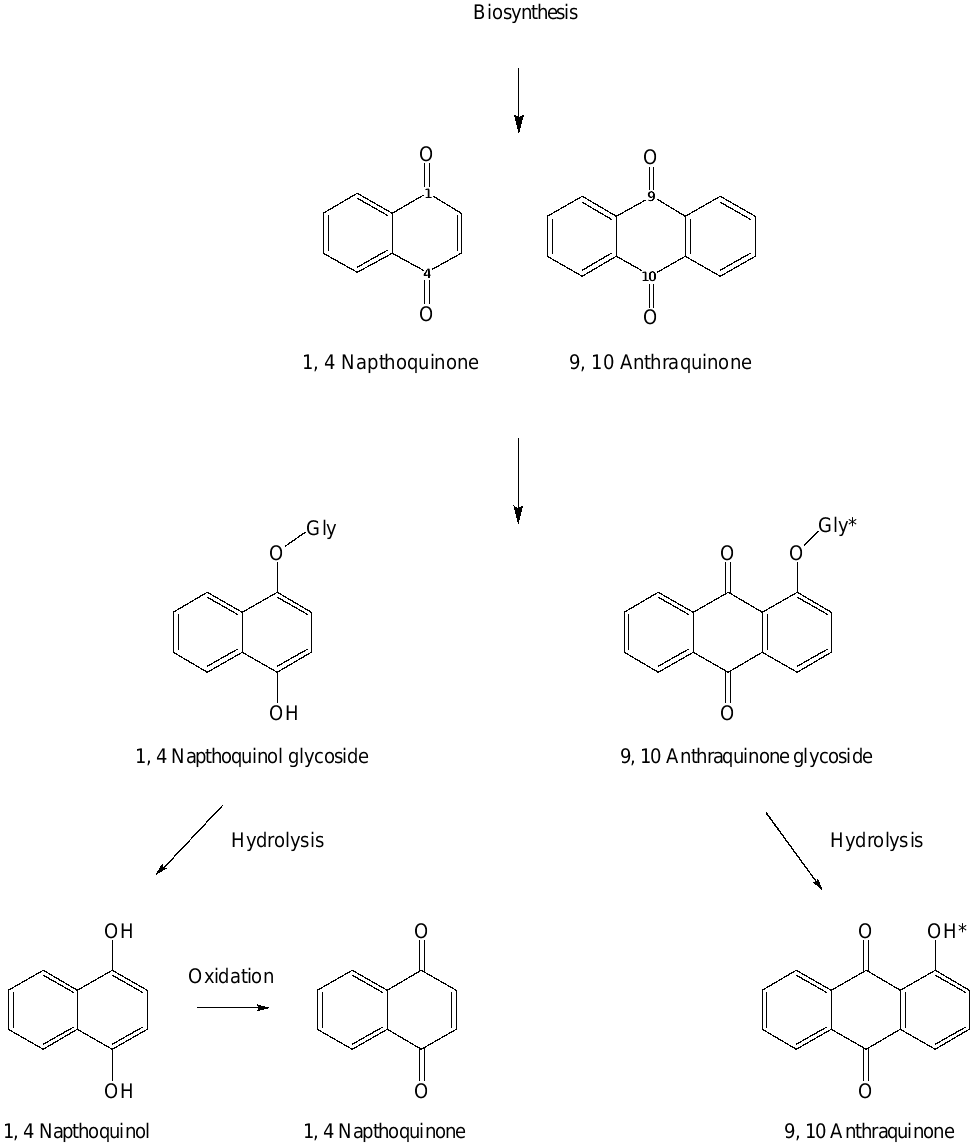

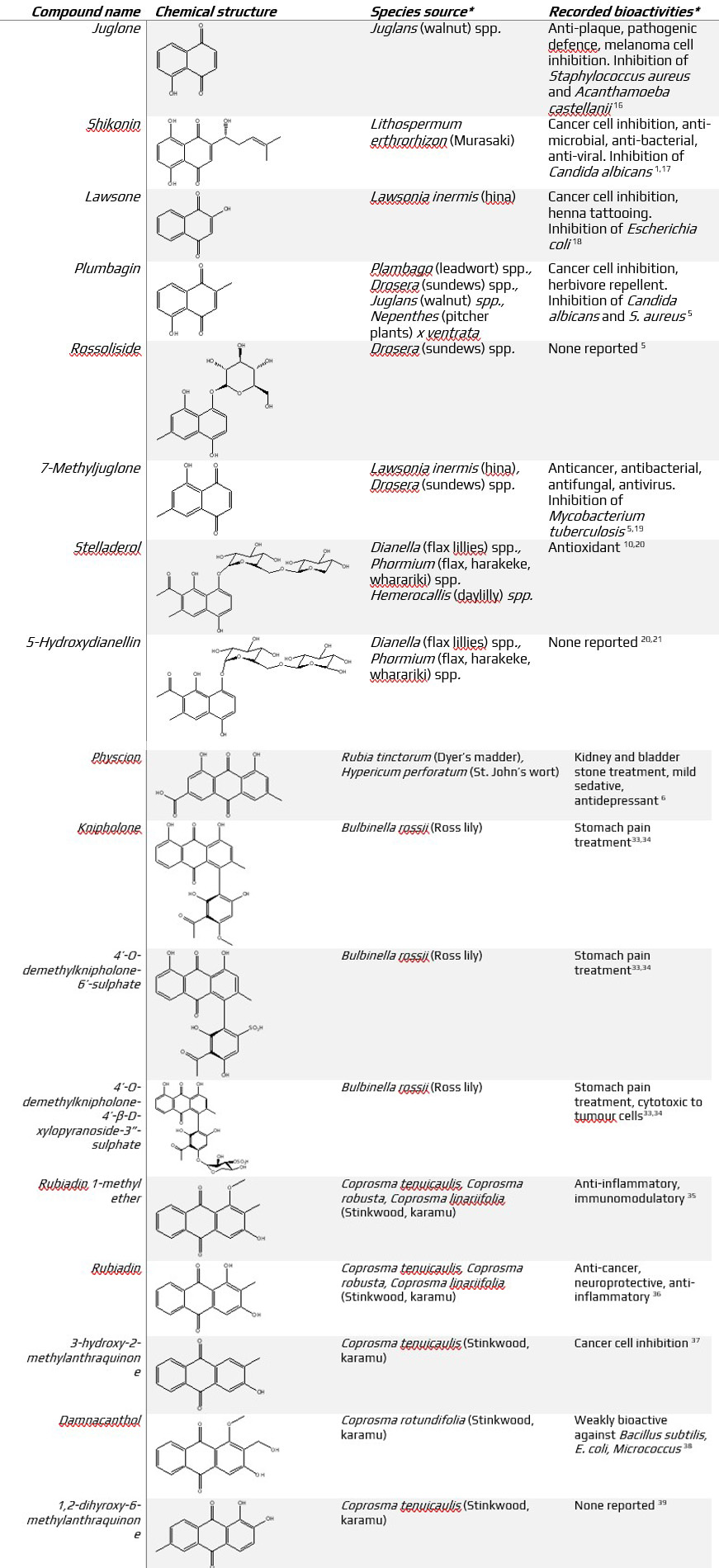

It has been long known that naturally occurring glycosidic compounds found in plants often end up being hydrolysed by enzymes, resulting in the release of an aglycone with a biological effect.1-3 The naphthoquinol (NQL-GLY) and anthraquinone glycosides (AQ-GLY) are a broad class of compounds in which this is often observed3-6 (Fig. 1), occurring across a range of genera and families including Impatiens (jewelweed, touch-me-not, snapweed), Juglans (walnut), Drosera (sundews), Dianella (flax lillies), Coprosma (Stinkwood/karamu) and Phormium (flax, harakeke, wharariki).

These glycosidic compounds are commonly characterised by a 1,4-di-hydroxy or 9,10-quinone aromatic ring system (Fig. 1) with a substituted sugar moiety and an array of varying functionality, including hydroxyl, methoxy, and long chain fatty acids.

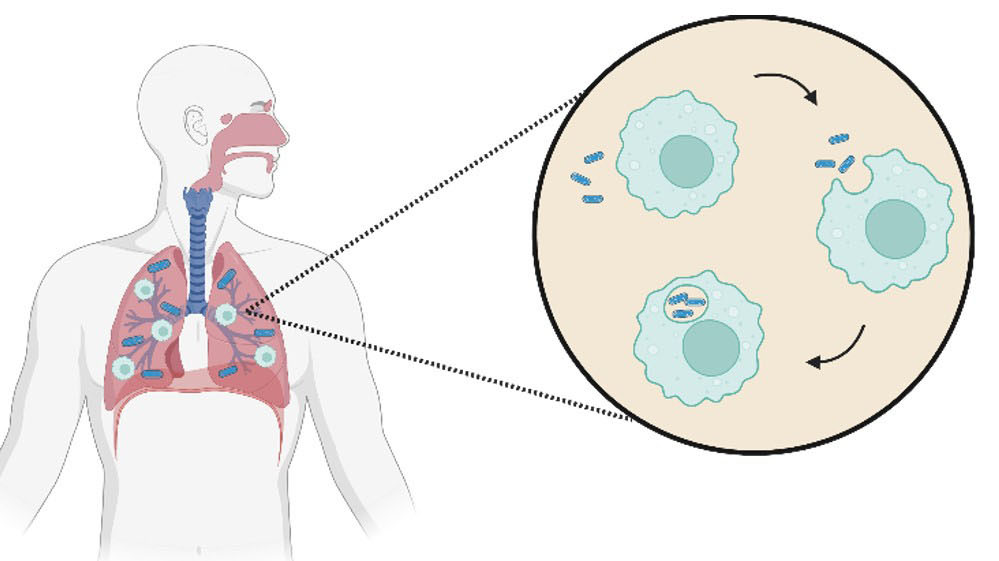

These water soluble polyaromatic QL/Q-GLYs are often stored in the vacuoles of plant cells where they can be released as a defense mechanism against herbivore attack, potentially preventing further damage to the plant.7 This damage (usually a result of biting/maceration of leaf tissue) causes the activation of enzymes or a change in pH eventuating in the enzymatic or acidic hydrolysis of these NQL-GLYs and AQ-GLYs into corresponding aglycones (Fig. 1) with a diverse number of biological effects (Tables 1 & 2). Not only can these compounds be used to ward off would-be predators, but they can also be allelopathic, such as in the case of walnut/Juglans, stunting and weakening nearby competing plant species.8 In the case of the NQLs, the bioactive aglycones can undergo a change in functionality and spontaneously oxidise to naphthoquinones (NQs) (Fig. 1), with further biological effects,2,3,6,9 often antimicrobial in nature.

With this defensive capability, it is unsurprising then that some of these glycosides also show human medicinal potential, such as stelladerol and the emodin and chrysophanol glycosides10 (Tables 1 & 2). AQ-GLYs tend to show a similar level of bioactivity to their aglycone counterparts, but the same cannot be said for the NQL-GLYs. The NQL aglycones and oxidation products (NQs) have a noticeably higher recorded bioactivity, with most of these glycosides exhibiting no measurable bioactivity11,12 (Table 1).

The hydrolysed and oxidised aglycone products – the NQs and AQs – are broadly bioactive. Lawsone, juglone, and 7-methyl-juglone are known for their cytotoxicity against cell lines, including cancer cells, and bioactivity against bacteria and viruses (Tables 1 & 2).

What is of even greater interest is how consistently these plants and the NQs / AQs are linked to ancient traditional and indigenous uses. There have been many reports on these plants’ connections to their constituent compounds’ medicinal properties and traditional and indigenous applications. With this trend in mind, it stands to reason that with the abundance of endemic Aotearoa plants used in traditional Māori medicine (rōngoa), that there may be NQL-GLYs, AQ-GLYs and aglycones / oxidation products present in our native flora.

Biosynthesis of 1,4 naphthoquinones, 9,10 anthraquinones and their quinol/quinone glycosides

While some of the biosynthetic pathways and subsequent metabolism of these 1,4 NQs and 9, 10 AQs are known, others remain a mystery. In a review of the biosynthesis and molecular action of these compounds,2 it was suggested that 1,4 NQs were biosynthetically created through multiple pathways; the o-succinylbenzoate pathway; the 4- hydroxybenzoic acid/geranyl diphosphate pathway; the acetate-polymalonate pathway: the homogentisate/mevalonic acid (MVA) pathway; and the futalosine pathway. All produce 1,4 NQ and 9,10 AQ products.13,14 However, many AQs are also produced via the isochorismate-α-ketoglutaric acid-mevalonate pathway.14 This review also speculated on the potential for these compounds to be produced in this hydrolysed / oxidised form and then biosynthetically coupled to a water soluble compound (such as a glycoside) for detoxification and storage.15 Upon predation or consumption, enzymatic hydrolysis/ acid hydrolysis causes the release of the hydrolysed sugarless active form.

Metabolism and biological effect

The complexity and functionality of these hydrolysis products lead to a variety of bioactive effects. The reactivity of these compounds has been observed to influence the metabolism of plants through their production of reactive oxygen species, thiol depletion, alkylation / arylation of proteins, DNA damage and genotoxicity.2

Table 1 (below). Structure, source and bioactivity of naphthoquinones, napthoquinol glycosides and related compounds from the literature cited in this article. * not an exhaustive list +1, 8 dihydroxynaphthalene compounds commonly isolated alongside the naphthoquinones and naphthoquinol glycosides

Allelopathy is one of these observed bioactive effects: 1,4 NQs such as juglone, shikonin, lawson and plumbagin all have a phytotoxic effect on neighboring competing plants, secreting and leaching 1,4 NQs into the environment. These compounds can be taken up by neighboring plants inducing the phytotoxic effect.2 Juglone and plumbagin induce ROS (reactive oxygen species) production on tobacco BY-2 cells inciting programmed cell death, and juglone induced oxidative damage to the apical meristem of lettuce plants.2 These 1,4 NQs have also been noted to cause oxidative distress and thiol disruption in microorganisms such as bacteria and fungi.2

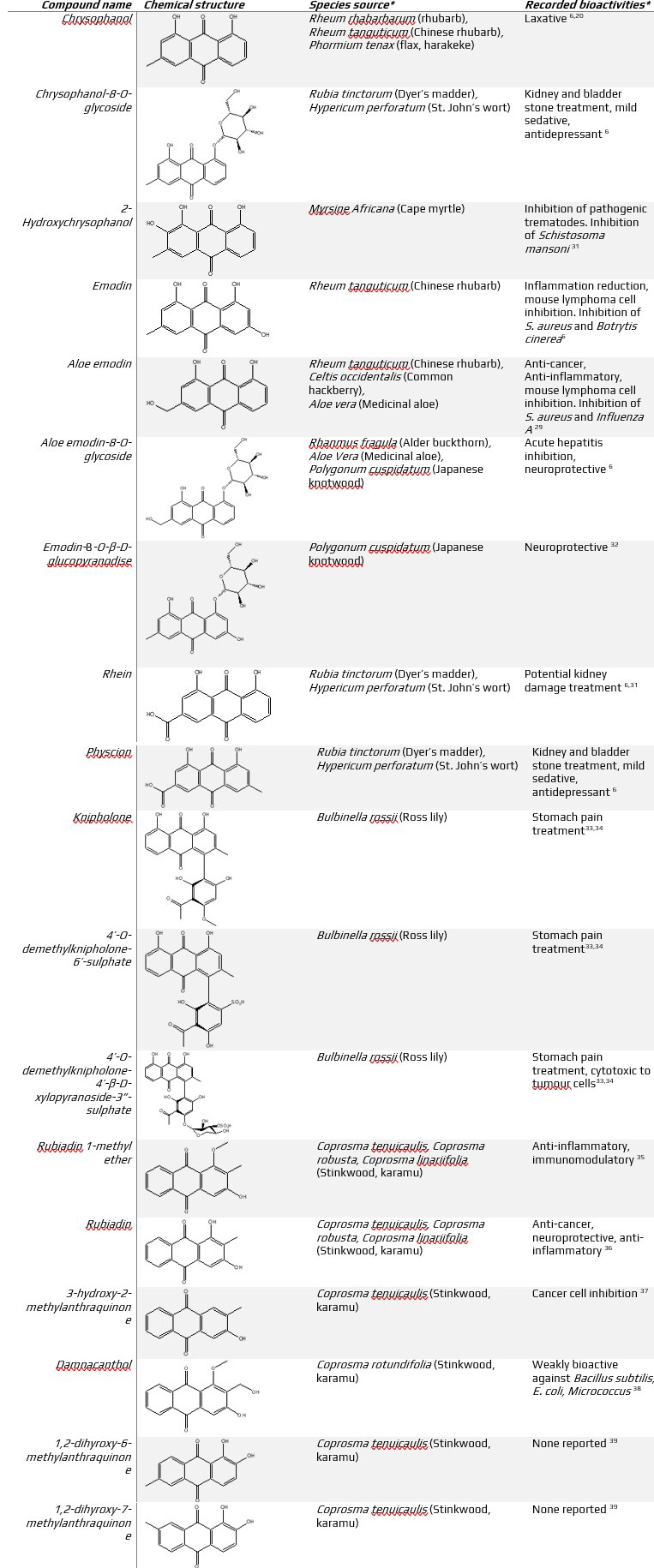

The 9,10 AQs (Table 2) also display a variety of biological effects, usually impacting the mammalian digestive and urinary systems. Most of the 9,10 AQs have laxative effects in mammals6 but also have antibacterial properties such as emodin on Escherichia coli.13 A review of aloe emodin highlighted an abundance of bioactivity; being anti-viral, anti-bacterial, anti-cancer and anti-inflammatory.29 Anti-inflammatory activity is often reported for these AQs.6,15,30

Table 2 (below). Structures, source and bioactivity of anthraquinones and anthraquinone glycosides discussed in this article

*not a complete list

Complexity and functionality

Variation in complexity and functionality within these classes of compounds is extensive. Simply looking at glycosides, sugar moieties can consist of mono or di-glycosylated structures comprised of combinations of a range of sugars, including glucose, galactose, xylose, diospyrosides, β-glucopyranose and β-xylosepyranose.3 This change in simple sugar functionality is often cited as being a key factor in the enhancement of solubility and activity. Sugar substituted 1,4 NQs are usually in the quinol form. Changing the chromophore backbone of the compounds aids in identification through UV-vis and multi-wavelength detectors.

The ring structures themselves can also be heavily substituted and variable. Classically they include variations in methylation, oxidation, hydroxyl groups, aldehyde, methoxy, and even long, hydrophobic, unsaturated isoprenoid chains such as in vitamin K.24 Substitution on the aromatic backbone can be a key determinant of biological activity.3 Substitution can occur all around the ring structure (Table 1).

These aromatic ring structures can also be missing the key 1,4 NQ functionality, instead being simpler hydroxylated naphthalene rings (Table 1 - dianellin and musizin). These hydroxylated naphthalene rings, such as musizin, are commonly isolated alongside the NQs and AQs (Table 1 - dianellin and musizin). Further examples in functional group variation are seen in emodin, 2-hydroxy chrysophanol and chrysophanol (Table 2). Both emodin and 2-hydroxychrysophanol are cytotoxic whereas chrysophanol is a laxative.6,20,21 The primary difference between these three compounds is the addition of a hydroxyl group to the anthraquinone ring system.

Identification

Multiple different methods exist to identify NQs, AQs, NQLs, NQL-GLYs, and AQ-GLYS. These generally consist of HPLC (high-performance-liquid-chromatography), LC-MS (liquid-chromatography-mass spectroscopy) and NMR (nuclear magnetic resonance) spectroscopy. NQs and AQs vary slightly from compound to compound, but there are general consistent absorbances for quinone and quinol backbones. The NQs tend to have a strong absorbance around < 340 nm, and sometimes a small absorbance around 400 – 500 nm depending on the functionality. While this can be quite similar to the AQs, AQs generally absorb more strongly in the 400- 500 nm region, hence appearing yellow-red.14,40,41 With the addition of the sugar moieties, the chromophore change from the quinones to the hydrogenated quinols causes a characteristic shift in the UV-vis spectra to mainly below 300 nm.42

LC-MS can provide mass spectra of entire extracts, corresponding to library matches for known compounds and fragmentation patterns. When used in conjunction with pure reference samples and NMR, this can provide a lot of information on NQs, AQs, NQLs, NQL-GLYs, and AQ-GLYS in a plant extract.

NMR spectroscopy represents the gold standard identification method for purified NQs, AQs, NQLs, NQL-GLYs, and AQ-GLYs. Generally they have characteristic shifts in the aromatic region (~6-8 ppm, 1H NMR), and downfield broad OH and hydrogen bonded signals (~10 ppm, 1H NMR) due to the 1,4 and 9,10 phenolic group interaction with neighbouring hydroxyls on the ring system.20,21 These are then easily distinguishable between glycosides and aglycones with sugar signals appearing up field around 5-3 ppm (1H NMR).20,21

Thin layer chromatography (TLC) is a method for qualitative identification. Many library and reference TLC methods exist for natural products which detail mobile phases for classes of compounds. In particular, TLC methods differentiate between the AQ-GLYs and their aglycones, which is also true for the NQs and NQL-GLYs.43

Often a combination of techniques (HPLC, LC-MS, NMR, TLC) is required to garner meaningful information from plant extracts.

Isolation

Isolation of these compounds ranges in difficulty, with some compounds purified after one treatment, but others exhibiting difficult co-elution and low mg yields.44 General procedures include RP (reverse phase) chromatography of a crude extract followed by larger ratio (50:1 or higher) silica to plant matter on normal phase silica chromatography, and final purification by preparative HPLC. While this is conventional, the method of extraction can vary for target compounds. For a full mix of NQs, AQs, and the Q/QL-GLYs, ethanol or methanol are usually used. However, for non-polar aglycones, hexane and chloroform extractions have also been reported.20,22,44-46 Acetone and water combinations are additional extraction solvents used for targeted glycoside isolation.16,23

Other methods also include phase-separation techniques, utilising biphasic toluene or ethyl acetate / petroleum ether. Phase separation follows the extraction process (via methods mentioned previously or similar), potentially including a form of column chromatography prior to the phase separation.16 It has been noted that treatment of plant material can heavily impact the yield of the NQL-GLYs and AQ-GLYs. Lyophilisation (freeze drying) is a critical step in the isolation of some NQL-GLYs.44

Hydrolysis studies are also commonly used in isolation / identification of aglycones. The glycosylated NQLs and AQs are first isolated from the plant and then treated with either the plant’s natural glycosidase (also isolated from the plant), or a commercial enzyme or acid hydrolysis. This then releases the aglycone from the sugar moiety making it available for purification. This method can also be used to confirm biosynthetic pathways by analysing the release of aglycone, loss of glycoside, and then formation of oxidation product all via HPLC.5,16,44

Medicinal properties and uses

As previously mentioned, NQs, AQs, NQLs, NQL-GLYs, and AQ-GLYS have been highly valued by humans for centuries due to their medicinal applications.2 AQs can be used as laxatives, and both AQs and NQs can exhibit cytotoxic, antibacterial, antifungal, anti-inflammatory, anthelmintic and antiparasitic effects, perhaps the most common reason for their use in wound treatments as plant extracts.2,14,15,47 They can also cause oxidative stress and disrupt thiol metabolism in mammalian cells, e.g. juglone, 8-hydroxydroserone and rubioncolin C, which is particularly interesting in cancer cells [2, 26, 27].2,26,27

Another example of anti-cancer properties is vitamin K and its derivatives, the menaquinones (Table 1). These 1,4 methylated long chain NQs are not just important in the diet but have potent anti-cancer effects when tested against leukemia cell lines,24 with menaquinones having shown strong cell-killing capabilities.24 Glycosylated NQLs16,48,49 were generally observed to have lower recorded bioactivity and inhibition of microorganisms.1,12,18,19,50-52

The extent and details of plant-derived 1,4 NQs pharmacological effects are broad, and well beyond the scope of this review. The interested reader is referred to the many detailed review articles that delve into the details of their pharmacology.2,3,11,12,51-53

As a consequence, NQs and AQs are garnering more attention for future and new medicinal applications, seen in the number of synthetic programs aiming to generate new functional derivatives of these compounds. Lapachol is a low bioavailability 1,4 NQ, where introduction of a glucosyl group produced NQs with high activity against tumor cells.3 Pecan quinone derivatives with synthetically introduced acetylated sugar portions were found to be more active than those with free hydroxyls, and shikonin - the classic example of a cytotoxic 1,4 NQ, was used to further synthesise novel antitumour and antiviral compounds.3

Links to traditional uses

With all of this bioactive potential of 1,4 NQs and 9,10 AQs, questions remain. Where did this knowledge first come from? How do the chemical properties of these compounds link to traditional uses across the globe?

Juglone (Juglans spp - walnut) was long known for its medicinal uses before the development of the scientific method, let alone modern chemistry. A hardwood native to the eastern and central areas of North America, Juglans nigria (black walnut) was traditionally used as a mechanical tooth cleaning apparatus with indigenous people recognising it aided in tooth longevity and quality. These properties directly link to juglone’s anti-plaque, anti-bacterial, and tooth whitening effects.50

Another instance of traditional use is Lawsonia inermis, commonly known as henna and the source of the 1,4 NQs lawsone and 7-methyl juglone. This plant has seen a slew of applications in different traditional medicinal systems over centuries including Ayurveda, Unani, Persian, African, and South Asian tribal healthcare.18 Every piece of the plant is applied by at least one of these medicinal systems, with the most common being the leaves, usually prepared as a poultice. One example of its traditional medicinal application is oils in the treatment of ulcers and infections, applied topically to treat wounds, matching with the established literature on the anti-microbial, analgesic, and anti-inflammatory properties of 1,4 NQ lawsone and 7-methyljuglone19 (Table 1).

One example of these NQs linked to traditional medicines/uses is shikonin and the shikonin glycoside. Existing across the globe, murasaki (Lithospermum erthrorhizon) is a significant plant in traditional Japanese medicine. Shi-Un-Koh is an ancient muraskai ointment developed from the roots of the plant used in the treatment of hemorrhoids, frostbite and general wounds.54 The bioactives of shikonin and its glycoside align well with this traditional usage1 (Table 1).

Another example of traditional use is that of the oblong-leaved sundew (Drosera intermedia) in Europe.55 Oblong-leaved sundew contains another well-known NQ bioactive - plumbagin (Table 1).

These examples show the connection between NQs and NQL-GLYs and traditional indigenous people’s knowledge systems and uses of plants, but what of the 9,10 AQs and AQ-GLYs and, in particular, emodin, 2-hydroxychrysophanol and chrysophanol?

Chrysophanol is a commonly found laxative in rhubarb (Rheum rhabarbarum). A traditional Chinese medicine, rhubarb has been used for ~ 2000 years. The ancient Chinese noted the profound benefits of rhubarb root (rhizome) particularly in its treatment of rheumatism, fever and digestive issues.47 Aside from chrysophanol with its laxative effect, emodin, aloe emodin, rhein, physcion and their corresponding glucopyranosides have all been found in rhubarb.30 These AQs all produce immune and biological responses with great potential to be linked to traditional Chinese treatments15 (Table 2).

NZ taonga: Dianella, Bulbinella, Coprosma and Phormium

It is well known then that these bioactive and potentially bioactive NQs, AQs, NQLs, NQL-GLYs and AQ-GLYs have direct links to indigenous people’s traditional use of plants. How about in Aotearoa? Māori have extensive mātauranga (traditional knowledge) around the uses of New Zealand plants, including medicinal (rōngoa) applications. Are there NQs and AQs in Aotearoa taonga (sacred) plants? Unsurprisingly – yes. The genus Dianella (Table 1) has seen a slew of these compounds isolated from it, including dianellin, its aglycone musizin, stypandrone and stypandrol,20,22,23,46,56,57 while Bullbinella contains AQ-GLYs of the chrysophanol AQ.34

However, there are scant recorded traditional uses of endemic Dianella and Bulbinella (usually mentions of potential use as dyes or weaving fibers) in Aotearoa. Are there other native plants with these compounds that have potential links to traditional uses or medicines? Once again, the answer is yes – Phormium and Coprosma.

Coprosma, known as karamu by Māori, is a well-known rōngoa plant where the root, leaves or bark were boiled and consumed as a treatment for bowl, bladder, kidney, and urinary issues58 in a similar manner to previously mentioned indigenous plants, e.g. rhubarb (Table 2), with both plants containing a variety of AQs.39

The endemic genus Phormium includes Phormium tenax and cookianium, known by Māori as harakeke and wharariki. These native flaxes, in particular harakeke, are used in weaving and fiber production and were vital to human survival in Aotearoa before the introduction of European fabrics and textiles.58 However, few people outside of Māoridom know it was also used as a traditional medicine, primarily as a wound treatment and purgative. A lot of this rōngoa knowledge of harakeke has fallen out of use and been lost, but some is recorded in books and remembered by kaumātua (elders). These traditional uses include preparation of the heavily pigmented root or leaf bases of the plant boiled in water, steeped in water, or roasted and the resultant poultice applied directly to a wound or ingested for a purgative effect.

So what of the chemistry? A short paper in the 1980s,45 an unpublished thesis59 and current research by the author of this article all reported further NQs, AQs, and NQL-GLYs from harakeke and wharariki (Table 1 and 2). Not only are these compounds present in the form of glycosides (stelladerol, 5-hydroxydianellin), NQs (stypandrone, musizin) and AQs (chrysophanol), but they also seem to have potential links to the harakeke rōngoa listed previously. The majority of these compounds, including both glycosides and sugarless AQs and NQs, have reported anti-bacterial, anti-viral, antioxidant, and laxative (purgative) properties.57 These compounds share similar biological effects to other wound-treating NQs and AQs, previously listed such as juglone, lawsone and shikonin, making a solid case for the potential link of this chemistry to traditional wound healing. The well-known laxative effect of AQ aligns well with the known purgative properties of Phormium.

Future work

While this work has been carried out on the isolation and identification of these compounds of interest from endemic Phormium, Coprosma, Dianella, and Bulbinella, it is far from nearing the end. It is certain that not all of the 1,4 NQs, 9,10 AQs, NQL-GLYs, and AQ-GLYs have been isolated from these species in Aotearoa, and little to no work has been done on geographic variation or the effects of plant age, environment and cultivars. Nor have molecular maps been designed for displaying dispersity within the plants.

Speculative biosynthesis exists for these compounds in general, but no work exists on the biosynthesis of these compounds specifically in Phormium, Coprosma, Dianella and Bulbinella. Future work could also look at the storage mechanism of these compounds in Phormium and Coprosma and how that relates to traditional extraction and preparation methods – do these methods preferentially extract glycosides or the aglycones which are generally considered more active? If different preparation methods preferentially extract these compounds, how does that link to traditional remedies and storage? Is a mixture of GLYs and aglycones better for wound healing or bowel / urinary treatments in some instances or is preferential extraction better? What other endemic taonga exist that have these compounds? How are they involved? How does tīkanga (traditional protocols, e.g maramataka – the Māori luna calendar - harvest indicators) affect the chemistry? Many questions remain to be answered.

Conclusions

It is clear that NQs, AQs, NQL-GLYs, and AQ-GLYS are interesting and diverse molecules, steeped in ancient traditional remedies, with a broad range of medicinal properties that depend on functionality. They present exciting opportunities for further investigation, such as development of new medicines, and may even prompt organic chemists to try their hand at synthesising more pharmacologically beneficial variants. They offer a deep connection between chemistry and traditional knowledge that provides all people involved with the opportunity for culturally vibrant projects with real world context. This field of research also opens opportunities for authentic collaboration between chemists and indigenous groups.

References

- Biswal, S.; Bishwal, B.K. ChemistrySelect 2024, 9(45).

- Widhalm, J.R.; Rhodes, D. Hortic Res 2016, 3, 16046.

- Shen, X. et al. Bioorganic Chemistry 2023, 138, 106643.

- Budzianowski, J. Phytochemistry 1995, 40(4),1145.

- Budzianowski, J. Phytochemistry 1996, 42(4), 1145-1147.

- Malik, E.M.; Müller, C.E. Medicinal Research Reviews 2016, 36(4), 705-748.

- Dávila-Lara, A. et al. Plos One 2021, 16(10), e0258235.

- Meyer, G.W.; Bahamon Naranjo, M.A.; Widhalm, J.R. Journal of Experimental Botany 2020, 72(2), 167-176.

- Oku, H.; Kato, T.; Ishiguro, K. Biological & Pharmaceutical Bulletin 2002, 25(1), 137-139.

- Cichewicz, R.H.; Nair, M.G. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2002, 50(1), 87-91.

- Li, B. et al. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 2019, 67(10), 1072-1075.

- Dias, D.A.; Silva,C.A.; Urban, S. Planta Med 2009, 75(13), 1442-1447.

- Zhou, T. Physiology and Molecular Biology of Plants, 2021, 27(11), 2487-2501.

- Seigler, D.S. In: Springer US: Boston (Ed.: Seigler, D.S.),1998, 76-93.

- Xin, D.; Molecules 2022, DOI: 10.3390/molecules27123831.

- Duroux, L.; Biochemical Journal 1998, 333(2), 275-283.

- Hook, I.; Mills, C.; Sheridan, H. Elsevier, 2014, 119-160.

- Joshi, C.S.; Kavan; Odedra Kunal N; Jadeja, B. A. Plant Biota 2025, 1.

- Mbaveng, A.T.; Kuete, V. Afr. Health Sci. 2014, 14(1), 201-5.

- Dias, D.A.; Silva, C.A.; Urban, S. Planta Med 2009, 75(13), 1442-1447.

- Cichewicz, R.H.L.; Kee-Chong.; McKerrow, J H.; Nair, M G. Tetrahedron 2002, 58(42), 8597-8606.

- Colgate, S.M.; Dorling, P.R.; Huxtable, C.R. 1987

- Briggs, L.H.; Briggs,L.R.; King, A.W. N. Z. J. Sci. 1975, 18(4), 559-63.

- Yaguchi, M. et al. Leukemia 1997, 11(6), 779-787.

- Wang, Z. et al. Phytochemistry 2018, 145,153-160.

- Bringmann, G. et al. Journal of Natural Products 2016, 79(8), 2094-2103.

- Abdissa, N. et al. Molecules, 2014, 19(3), 3264-3273.

- Hussain, H. et al. ARKIVOC 2007, 2, 145-171.

- Dong, X. et al. Phytotherapy Research 2020, 34(2), 270-281.

- Zhao, S. et al. Food Bioscience 2024, 62, 105426.

- Cichewicz, R.H. et al. Tetrahedron 2002, 58(42), 8597-8606.

- Wang, C. et al. European Journal of Pharmacology 2007, 577(1), 58-63.

- Kuroda, M. et al. J. Nat Prod 2003, 66(6), 894-897.

- Richardson, A.T.B.; Lord, J.M.; N.B. Perry. Phytochemistry 2017, 134, 64-70.

- Mohr, E.T.B. et al. Mediators of Inflammation 2019, 1, 6474168.

- Watroly, M.N. et al. Drug Design, Development and Therapy 2021, 15, 4527-4549.

- Sun, C. et al. Phytomedicine 2019, 61, 152848.

- Xiang, W. et al. Fitoterapia 2008, 79(7), 501-504.

- Briggs, L.H. et al. Journal of the Chemical Society, Perkin Transactions 1 1976, 16, 1789-1792.

- 40. Rodrigues, S.V.; Viana, L.M.; Baumann, W. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 2006, 385(5), 895-900.

- Anouar el H. et al. Springerplus 2014, 3, 233.

- Spruit, C.J.P. Recueil des Travaux Chimiques des Pays-Bas 1949, 68(4), 309-324.

- Wagner, H.; Bladt, S. Plant Drug Analysis. A Thin Layer Chromatography Atlas. Berlin: Springer, 2nd ed. 1996,

- Triska, J. et al. Molecules, 2013, 18, 8429-8439.

- Harvey, H.E.; Waring, J.M. J. Nat Prod 1987, 50, 767.

- Nhung, L.T.H. et al. Natural Product Research 2021, 35(18), 3063-3070.

- Wen, Y. et al. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2024, 15.

- Colegate, S.M.; Dorling, P.R.; Huxtable, C.R. Phytochemistry 1987, 26(4), 979-981.

- Ge, Y. et al. Metabolomics 2018, 14(10), 1-11.

- Sharma, M. Proceedings of the Indian National Science Academy 2022, 88(4), 601-616.

- Colegate, S.M.; Dorling, P.R.; Huxtable, C.R. Phytochemistry 1987, 26(4), 979-981.

- Nishina, A. et al. Journal of the American Oil Chemists' Society 1991, 68(10), 735-739.

- Li, X.-H.; McLaughlin, J.L. Journal of Natural Products 1989, 52(3), 660-662.

- Ito, E.; Munakata, R.; Yazaki, K. Plant and Cell Physiology 2023, 64(6), 567-570.

- Baranyai, B.; Joosten, H. Mires and Peat 2016, 18, 18.

- Cooke, R.G.; Sparrow, L.G. Aust. J. Chem 1965, 18(2), 218-225.

- Widyaning, E.A.R. I.; Timotius, K. H. Internation Journal of Herbal Medicine 2020, 8, 10-18.

- Riley, M. Maori Healing and Herbal. Paraparaumu: Viking Sevenseas N.Z. Ltd.1994

- Hindle, B.J. MSc thesis, University of Canterbury 1998.